|

|

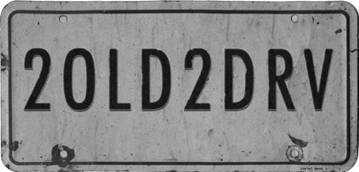

Driving Debate Fails the Vision Test

By

Joseph F. Coughlin, www.Boston.com

July 29, 2009

What is an older driver? Most reply 20 years older than they are. Scientifically we don’t know. But, does it matter? Despite misuse of statistics, older drivers are safe drivers. Most self-regulate - not driving at night, in highly congested places, or poor weather. They choose to forgo trips rather than take risks. They are most often the fatal victim of their own fragility rather than the killer of others.

Birthdays don’t kill, health conditions do. Tragedies show accidents trace back to drivers suffering from effects of chemotherapy, dementia, medication, or patterns of accidents ignored by others. Crashes linked to poor disease and medication management are too complex to be media-worthy. With 110 million Americans suffering from one chronic disease and 60 million suffering from two or more, health, not age, is the looming threat to safety.

Older driver testing is a simplistic and symbolic response to a complicated issue. There is no validated, affordable, or widely accepted “test.’’ The primary tool for assessing drivers is “what they look like coming through the door.’’ To do better, policymakers must be willing to commit long-term, significant resources to an overburdened agency that’s most closely associated in public minds with waiting in purgatory. Massachusetts should consider a strategy of testing annual samples of all drivers to identify impairment at any age.

Testing must be accompanied by policies that engage unwilling participants. Older drivers see testing as a threat to freedom and independence. Families, mostly adult children, avoid conversations about driving because of burdens it places on them. Physicians see themselves as public-health officials, not law enforcement officers. Legislators, stuck between safety and freedom, won’t commit the resources to be effective. Yet each group has a responsibility to take action to promote safe mobility.

Drivers and families should monitor personal well-being - including cognitive and physical fitness, medication, and changes in health. Families are the first line of safety and lifelines to mobility after driving. They are in the best position to intervene when health or patterns of incidents suggest problems. Families should plan ahead for mobility needs of loved ones - the number-one alternative to driving yourself is riding with someone else. And, when it’s time to have the conversation, most older drivers want to hear from loved ones who truly care, see them drive regularly, and have transportation plans supporting lifestyle, not just living.

Physicians should be provided with liability protection, training, and responsive systems for reporting concerns. Most general practitioners don’t have the knowledge to assess driving capacity of patients whose health may fall into gray areas. Proper training, medical-based screening, rehabilitation, and development of driver wellness approaches should be developed to support clinicians.

Driving is the glue that holds life together - before you do anything you have to get there first. Next-generation vehicle systems to enhance vision, reduce distraction, and warn drivers could revolutionize safety for vehicle occupants and pedestrians alike. Federal policymakers should encourage automakers to speed development and deployment of “intelligent’’ technologies improving driver safety across the lifespan.

The aging of the driver population is an opportunity to rethink community design and transportation systems. After driving or riding with a friend, walking is the most popular mode choice. Livable communities must include sidewalks, benches, lighting, even shade and shield from sun and rain, to encourage walking from childhood through adulthood. The state’s congressional delegation should support national programs providing resources to redesign public transportation and livable communities.

More than 70 percent of Americans over 50 live in areas where transit either doesn’t serve or doesn’t serve well. Transit-rich Boston is no exception. Paratransit is costly to provide and gives priority to medical and grocery trips, and not to other activities important to older people - simply getting out or visiting friends. Systems requiring booking a day, week, or more in advance, on a vehicle that screams “old man going to the mall,’’ are not real alternatives. Public transportation must be redesigned to go beyond its original intent of getting people to work, suburb to city, to serving everyone’s mobility needs across a lifetime in the city, and beyond.

There is a coming mobility gap. This isn’t a discussion about the old; it’s about all of us. If we choose to translate the current round of political passion into another discussion of “driver age and testing,’’ rather than how we can provide safe mobility for a lifetime, all of us should shop for a comfortable chair in retirement; we’ll be staying home for a very long time.

More Information on US Health Issues

|

|