back

|

|

Collecting What's Long Past Due

By John Moreno Gonzales, Newsday

January 19, 2004

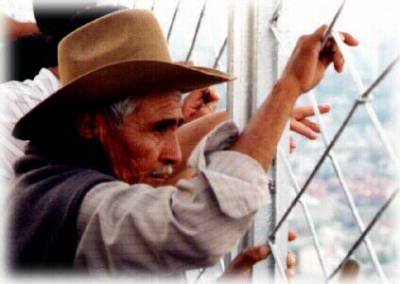

At age 83, the hands of Sotero Cervantes can be either powerful or weak after a life of work in the fields. They are mallets pounding on a table when he wishes to punctuate a statement, and leaves that tremble when he recounts sad memories.

"My life has been very hard, but how much harder would it be if I was not in the United States?" the hands say with a thud to the desk before him, when Cervantes is asked if his toil entitles him to any sympathy.

"Of the people that I knew, there are maybe eight out of a hundred who are still alive," the hands say with a quiver, when Cervantes remembers countrymen who worked by his side.

Cervantes, of a prominent nose, thick eyebrows and the workingman's hands, is living history. He is a former bracero, or strong arm, one of an estimated 4.5 million Mexican laborers granted temporary permits to work the planting fields, rail yards and docks of the United States from 1942 to 1964.

Filling jobs left vacant as American men fought wars for a nation enjoying unprecedented economic growth, the braceros' hourly pay was more often counted in cents than dollars. Their employers held powerful sway over their lives, able to deport them if they protested wages or working conditions, or to help them stay permanently in the United States if they were loyal. Their modest paychecks were often sapped through mandatory fees for food, shelter and in the first years of the program, retirement accounts that were supposed to be there when they returned home.

But even as Presidents George W. Bush and Vicente Fox of Mexico met this week to discuss sweeping proposals that once again tackle the immigration question, many of the oldest braceros are dying as they wait for what is long overdue. The 10 percent deducted from each paycheck from 1942 to 1949 for retirement savings disappeared in what the U.S. government says was lax administration by Mexican caretakers and what the Mexican government says was poor management by U.S. officials and banks.

"I never received a thing," Cervantes said during an interview at the offices of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization working with some of the 1,100 former braceros who have become the bedrock of the Mexican-American community in this northern California town of stretching farmland and modest starter homes.

It is a historical misdeed not overlooked by today's immigrants, who see Bush's recent guest worker proposal as little more than a modern-day version of bracero-like servitude. They question the wisdom of signing up to a new guest worker program if the U.S. and Mexican governments have yet to right the wrongs of a similar experiment generations ago.

"Under Bush's program, you work here for three years and then walk back to Mexico," scoffed Carlos Zuniga Jr., a 40-year-old construction worker who has been living illegally here for 25 years.

"My father was a bracero," he said while attending a packed immigration forum held by the friends committee. "And they still haven't paid them the [retirement] money they earned."

In March 2001, former braceros in California and Chicago sued the U.S. and Mexican governments, Wells Fargo Bank and three Mexican banks to recover the retirement savings, an amount advocates estimate at $500 million based on inflation and unpaid interest.

The Mexican government conceded that about 13,000 surviving workers have provided some proof of claim to the money. But in August 2002, a federal judge in San Francisco dismissed the suit, citing statutes of limitations and rules of jurisdiction.

As the Mexican defendants and their U.S. counterparts blamed each other for the lost funds, the California State Legislature passed a law in January 2003 that extended the statute of limitations in the case. The legislation prompted a reversal of the federal judge's earlier decision.

In light of the reversal, Fox offered each of the workers a $10,000 settlement last November. But the men, including Cervantes, called it insufficient and are proceeding with a court fight that could take years to be resolved though advocates say the elderly men are dying at the rate of one a week.

"It's not the money as much as it's a symbol of recognition," Doc Baird, a volunteer with the friends committee, said of the decision to continue the legal fight. "These are the people who fed our country and made it a better place to live through their sweat."

It is not only the lack of restitution for former braceros that makes cynics of modern immigrants; it is what happened after time expired on the old workers' permits.

Faced with a return to a homeland of crushing poverty and with little money saved, many of the workers remained illegally in the United States after their permits expired. Though they often had no trouble keeping work, the overstays prompted the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service to begin Operation Wetback, a plan designed to round up offenders in Texas and California.

According to INS records, the 1954 operation repatriated more than 1.1 million Mexicans. Though such a bluntly offensive moniker would not be used today, many immigrants see the tougher enforcement that is part of Bush's proposal as not far removed from the actions of 1954, and subsequent years of aggressive deportation.

"I was so lucky," says Jose Diaz, a former bracero who like Cervantes and others in the area was able to stay in the United States through the intervention of an employer.

Diaz, 64, with thick shoulders and fine hair that blows in the wind like wheat, has kept pictures and documents from his experience. They are on poster boards that stand belt-high and unfold to reveal years of hard work and resilience in local tomato fields.

On one board, his first contract is mounted next to pictures of men he once knew. Diaz said he was 18 when he signed up for the program in 1958 in Mexico and borrowed a travel fund of 300 pesos, about $30, from an uncle to reach California.

But after he fulfilled the contract with eight-hour shifts, five days a week, he hadn't earned enough money to pay his uncle back. Since his contracts required an annual renewal that could only be administered in Mexico, Diaz returned to his town near Mexico City in shame, arriving with a few cents in his pockets and a promise to try his luck again in the United States.

He renewed his contract for the next three years, along the way able to pay back the uncle and befriend an American farm owner who admired his work ethic and eventually made him a supervisor.

The late owner, Ernest Perry, offered in 1961 to write letters to Mexican and U.S. consular officials requesting that Diaz be granted permanent residency in the United States. Diaz returned to his homeland that year, and Perry sent the letter to the consulate in Mexico City, also instructing Diaz to go to the consulate and begin the application process.

Diaz went, but says when he arrived a Mexican official had sold his bosses' important letter of endorsement to a man of the same name. Meanwhile, Perry and his wife had filed for divorce, and it was unclear if the farm owner would keep his lands, let alone have a job waiting for Diaz upon arrival in the United States.

Months passed until Perry was finally able to resolve his ownership of the farm and send another letter seeking a permanent residency for Diaz.

More time passed before the process was complete. But Diaz entered the country not as a temporary worker, but legal resident, in 1962, working for Perry until 1978.

Diaz married his wife, Maria, in Mexico in 1963 and brought her to the United States, where they raised six children in a three-bedroom house not far from the fields where he first labored.

Still, Diaz says he does not blame today's immigrants for their skepticism toward a guest worker program. He said few employers are as kind as his, and today the process to obtain residency is far too difficult.

"Those immigrants who are here should be allowed to stay," he said. "The jobs are here for them, and their lives are hard enough."

Diaz then folded up the poster boards, the old records and pictures arguing that his last sentence has always been true.

Copyright © 2002

Global Action on Aging

Terms of

Use | Privacy

Policy | Contact Us

|