|

|

A Tough Sell: Japanese Social Security

By James Brooke, The New York Times

May 5, 2004

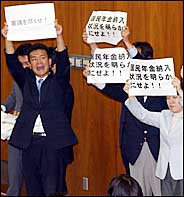

Opposition members of Parliament during a social security debate waved placards saying, "Disclose pension payment." Many Japanese, including a leader of the opposition, have missed payments.

Opposition members of Parliament during a social security debate waved placards saying, "Disclose pension payment." Many Japanese, including a leader of the opposition, have missed payments.

With almost 40 percent of young workers skipping out on their social security payments, Japan started an advertising campaign featuring a popular actress, who sternly lectured subway riders: "So you don't mind crying in the future? Pay now. Or later, you don't get paid."

Then, enterprising reporters discovered that the 20-something actress, a self-employed worker, had neglected to pay into the national pension system for years.

But as Parliament prepares to vote Thursday on legislation to increase pension contributions gradually by 35 percent, other enterprising reporters have uncovered that seven ministers, a third of Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's cabinet, also have neglected to pay into the National Pension Plan.

With the ministers of economy, of finance and of trade and industry on the list, the opposition thought it finally had an issue to take to voters in elections this summer. Then, through more enterprising reporting, it was discovered that Naoto Kan, leader of the opposition, had neglected to pay into the plan for 10 months in 1996, when, as health minister, he was in charge of the national pension system.

"This pathetic political theater leaves us more dumbfounded than angry," an editorial in Asahi Shimbun stated. This liberal newspaper printed a cartoon showing a dozen bureaucrats cavorting on a double-decker wooden festival float, marked "Public Pension System." As the four porters, labeled "Public," staggered bug-eyed under this enormous weight, the bureaucrats did a fan dance, singing a jolly chorus: "Trust us, trust us."

But, according to a poll conducted in March by the Mainichi newspaper, 81 percent of Japanese respondents in their 20's said they "don't trust" the national pension system. For people in their 30's, the figure was 74 percent. For all adults, the "don't trust" group was 60 percent.

"Those ministers not paying their premiums certainly exacerbated the already skeptical public view of the system," Shingo Hirata, a 21-year-old economics student said here on Wednesday. "The existing system is not sustainable and drastic change is needed."

Yusuke Tomofuji, a classmate agreed, saying: "Honestly, I cannot trust the current pension system. I am sure that system will soon go bankrupt. It is almost unspoken common sense, and this series of incidents showed that."

The lack of trust derives from the widespread understanding that Japan's work force is already shrinking.

At present, Japan has one of the world's lowest birth rates. On Tuesday, the government's statistics bureau announced that the number of children aged 15 or under had fallen by 200,000 over the last year, to 13.9 percent of the population, the lowest level on record. By contrast, the comparable American figure is 21 percent.

In 1950, when the national pension system started to take shape, 35 percent of Japan's population was 15 years or younger, and 4.9 percent of Japanese were 65 or older. Since 1970, the number of workers supporting a pensioner has dropped from 8.5 to about 3.5.

If trends hold up, the elderly population will match the working population in 2044, according to Tadashi Nakamae, president of Nakamae International Economic Research. Birthrates could stay low for years to come, as many Japanese women are on a marriage strike. As of 2000, 54 percent of Japanese women in their late 20's were single, more than double the 1980 level of 24 percent. The comparable rate in the United States today is about 31 percent. In contrast to the United States, Japan has few births outside of marriage; at last count, 99 percent of Japanese babies were born in wedlock.

Without future workers in the pipeline, many young workers view the mandatory pension system as a one-way intergenerational asset transfer.

Where will the money come from, they ask, to pay for their own retirements 40 years down the road? The Nikkei newspaper calculates a roughly $4 trillion gap between the government's future pension obligations and its future contributions. With politicians determined to maintain a level of government spending not related to tax receipts, Japan is already the most indebted of the major industrialized nations.

Taking one step, Parliament is to approve in coming days the plan to raise premium payments gradually by about one third and to cut pension benefits by 15 percent. Officials are also studying ways to simplify the system's complicated rules, a trap that apparently caught many of the ministers.

To keep the program solvent through 2012, "they are 85 percent there," Robert A. Feldman, chief economist for Morgan Stanley Japan, said Wednesday. To keep Japan's pension system solvent and its living standards high, he said, the nation needs more immigration, more free market economic policies and an annual rate of capital investment of 4.3 percent a year.

But the problem will be daunting 20 years down the road, when Japan shifts from the demographics of Florida, to the demographics of a Florida retirement community.

"Then, depreciation is the only way out," Tony Sorrenti, an international economist here, predicted on Wednesday.

With elderly voters displaying increasing political power, he said, politicians will be reluctant to cut benefits deeply or to raise retirement ages, or to increase premiums by 50 percent. Instead, he predicted the inflation option will become more and more attractive, and government officials of the future will simply print money to meet

obligations.

|

|