|

|

In Rural China, River Turns Bitter and People Die

By Jim Yardley, The New York Times

September 13, 2004

"Google"

Image

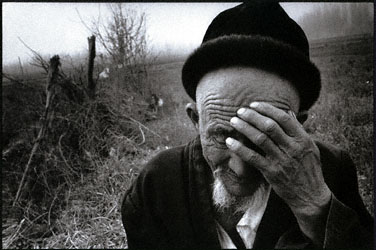

Wang Lincheng began his accounting at the brick hut of a farmer. Dead of cancer, he said flatly, his dress shoes sinking in the mud. Dead of cancer, he repeated, glancing at another vacant house.

Wang, head of the Communist Party in this village, ignored a June rain and trudged past mud-brick houses, ticking off other deaths, other empty homes. He did not seem to notice a small cornfield where someone had dug a burial mound of fresh red dirt.

Finally, he stopped at the door of a sickened young mother. Her home was beside a stream that had turned greenish-black from dumping by nearby factories - polluted water that had contaminated drinking wells. Cancer had been rare when the stream was clear, but last year cancer accounted for 13 of the 17 deaths in the village.

''All the water we drink around here is polluted,'' Wang said. ''You can taste it. It's acrid and bitter. Now the victims are starting to come out, people dying of cancer and tumors and unusual causes.''

The stream in Huangmengying is one tiny canal in the Huai River basin, a vast system that has become a grossly polluted waste outlet for thousands of factories in central China. There are 150 million people in the Huai basin, many of them poor farmers now threatened by water too toxic to touch, much less drink.

Pollution is pervasive in China, as anyone who has visited the smog-choked cities can attest. On the World Bank's list of 20 cities with the worst air, 16 are Chinese. But leaders are now starting to clean up major cities, partly because urbanites with rising incomes are demanding better air and water. In Beijing and Shanghai, officials are forcing out the dirtiest polluters to prepare for the 2008 Olympics.

In contrast, the countryside, home to two-thirds of China's population, is increasingly becoming a dumping ground. Local officials, desperate to generate jobs and tax revenues, protect factories that have polluted for years.

Refineries and smelters forced out of cities have moved to rural areas. So have some foreign companies, to escape regulation at home.

The losers are hundreds of millions of peasants already at the bottom of a society now divided between rich and poor. They are farmers and fishermen who depend on land and water for their existence.

In July and August, officials measured a 132-kilometer, or 82-mile, band of polluted water moving through the Huai basin. China rates its waterways on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being too toxic even to touch. This water was rated 5. For fishermen, it may as well have been poison. ''If I had wanted to, I could have gone on the river and filled a boat with dead fish,'' said Song Dexi, 64, a fisherman in Yumin. ''It was smelly, like toilet water. All our fish and shrimp died. We don't have anything to live on now.''

The Huai was supposed to be a Communist Party success story. Ten years ago the central government vowed to clean up the basin after a pollution tide killed fish and sickened thousands of people. Three years ago, a top Chinese official called the cleanup a success.

But the Huai is now a symbol of the failure of environmental regulation in China. The central government promotes big solutions but gives regulators little power to enforce them. Local officials have few incentives to crack down on polluters because their promotion system is based primarily on economic growth, not public health. It is a game that leaves poorer, rural regions clinging to the worst polluters.

Few places bear that out more than eastern Henan Province, which includes Huangmengying. The isolated region has tanneries, paper mills and other high-polluting industries dumping directly into the rivers.

One of the biggest polluters is Lianhua Gourmet Powder, China's largest producer of monosodium glutamate, or MSG, the flavor enhancer used in many processed foods and in cooking. But the company's political influence is so vast that environmental regulators who have tried to challenge the company have done so in vain.

The Huai River basin has neither the history of the Yellow River nor the mystique of the Yangtze. Yet the Huai, with its spider's web of canals and tributaries, irrigates a huge swath of China's agricultural heartland.

Farmers once spent lifetimes tilling the same plot of corn or wheat. But in the past decade, millions of farmers, unable to earn a living from the land, have left Henan for migrant work in cities, leaving behind villages of old people and young mothers.

Epidemiological research for cancer in the Huai basin is scant. None has been done in Huangmengying. Nor does any scientific evidence prove that pollution is causing the rising cancer rate. What is clear is the wide range of pollutants, from fertilizer runoff to the dumping of factory wastes.

But Dr. Zhao Meiqin, chief of radiology at the county hospital, said cancer cases in the area rose sharply after heavy industry arrived in the 1980s and '90s. Before, the area had about 10 cases a year. ''Now, in a year, there are hundreds of cases,'' she said, putting the number as high as 400, mostly stomach and intestinal tumors. ''Originally, most of the patients were in their 50s and 60s. But now it tends to strike earlier. I've even treated one patient who is only 7.''

Zhao said most cancer patients came from villages close to the factories along the Shaying River, a major tributary in the Huai basin. Wang, the village party chief, also said the highest concentrations of cancer were found in the homes closest to the village stream, which draws its water directly from the Shaying.

Health problems began appearing slowly in the early 1990s. Wang said he learned that the water was severely polluted after an environmental official came on a personal visit. Farmers also began complaining that their fields were producing less grain because of polluted irrigation water.

Today, pollution corrodes daily life here. Farmers too poor to buy bottled water instead drink well water that curdles with scum when it is boiled. Xiao Junhai is 57 but looks two decades older. In June, he shivered under a quilt in a dark room, summer flies flitting at his head, cancer knotting his stomach. He could not lift himself from his crude bed.

''I grew up drinking the water here and I still drink it,'' he said. ''I don't know what pollution is, but I do know it means the water is bad.''

His daughter, Xiao Li, 24, anguished over the dilemma that her father's illness had thrust upon her. She says her father takes traditional Chinese remedies and eats rice porridge because the family cannot afford treatment. If she returned to her migrant job on the coast, in Hangzhou, she might earn enough money to pay for treatment. But no one else can care for him.

''The water in the river used to be clean, but now it's black and changing colors all the time,'' she said. ''The water is being destroyed.''

Lianhua Gourmet Powder is based in Xiangcheng, upstream from Huangmengying. It is the area's largest employer, with more than 8,000 workers, and the largest taxpayer in Xiangcheng.

For Henan Province, Lianhua Gourmet is a signature company, the biggest producer of MSG in China. An analysis by a Chinese credit rating service, Xinhua Far East, found that in 2001 the factory produced more than 133,000 tons of MSG and has plans to raise production to 200,000 tons.

Under any circumstances, the company's sheer size would translate into significant political clout. But Lianhua, basically, is the government. Lianhua is traded on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, but according to the credit analysis, its majority stockholder is a holding company owned by the Xiangcheng city government.

This type of government-controlled enterprise is not unusual in China, but the potential for a conflict of interests is glaring. The production of MSG leaves potentially harmful byproducts, including ammonia nitrate and other pollutants. A damning report last year by the State Environmental Protection Administration said Lianhua had dumped 124,000 tons of untreated water a day through secret channels connected to the Xiangcheng city sewage system. The water eventually flowed into the Shaying River, almost quadrupling pollution levels. ''This constitutes a grave threat to the lives and livelihoods of people downstream,'' the report stated. Officials at Lianhua did not respond to repeated written and telephone requests for interviews. Neither did officials in Xiangcheng nor those with Henan Province.

But one retired local Communist Party official said party cadres had always protected Lianhua. He said a son-in-law of a Lianhua chief executive once even headed the city's environmental protection bureau.

The 10th anniversary of the government's promise to clean up the Huai had become a major embarrassment for the Communist Party. Roughly $8 billion had been spent to improve the basin, but the State Environmental Protection Administration concluded this year that some areas were more polluted than before.

China's press, often given freer rein on environmental issues, published critical articles over the summer. Even tiny Huangmengying got attention: a crew from state television visited in July. Officials, fearing a humiliating expose, hurriedly started digging a deeper well for the village. But the gesture was dwarfed by what Henan officials did for Lianhua.

For more than a year, the company had been in financial trouble, suffering from bad investments and a slowdown in the MSG market. For months, banks pressured it for roughly $217 million in unpaid loans.

The Henan Province government stepped into the breach. The Henan governor, Li Chengyu, organized a meeting at Lianhua headquarters in July to devise a plan to save the company. The Henan government also gave the company more than $25 million.

In Huangmengying, Wang again visited Kong, the young mother with cancer, who was also struggling to survive. Her resolve in June to forgo chemotherapy had withered with her health by August. She was pale and coughing as she explained that she had again borrowed money for treatment. She would leave in a few days.

But it meant that she could not pay her sons' school fees for the fall semester. Her husband could not find work and had no money to send. And the friends who had loaned her money said they could loan her no more. ''I'm scared,'' she said.

Only an hour earlier, Wang had been walking to visit Kong when a woman rushed up and knelt in a formal kowtow, touching her lips against the dirt. Her husband had dropped dead. Doctors had examined the body and discovered a tumor. She needed Wang to help with funeral arrangements. He asked where she lived.

In a small brick hut, about 45 meters, or 150 feet, from the stream, answered the woman, Liu Sumei.

Liu, 50, led Wang to a friend's home, where her husband's body lay in a coffin under a large poster of Mao Zedong. Liu had not known her husband had cancer, only that he was in poor health. But in Huangmengying, she said, poor health is not unusual. ''Every family has someone who is sick,'' she said ''all the neighbors.''

|

|