|

|

Geezers, Gerries and Golden Agers

By Geoffrey Nunberg, The New York Times

March 28, 2004

Not long ago, when a 20-something New Yorker told me, "I'm going to grandma's place in Florida to spend a week with the gerries," it took a moment to realize that the word was a truncation of "geriatric." If you thought he was referring to Germans, he might have been referring to you.

It's too soon to tell whether "gerry" will catch on. But it's normal for the generation that's coming of age to coin names for the one that's passing from center stage, not just in its slang, but in its official vocabulary as well.

Recently, the Progressive Policy Institute held a panel to promote its proposal for a Boomer Corps, a national service program for older Americans. The name was chosen to suggest a range of activities broader than those traditionally associated with retirees. But some people have worried that the connotations of boomer might become more derogatory as people over 65 come to constitute a quarter of the population, increasing the economic burden of Social Security.

It wouldn't be the first time that words for old people went from positive to disparaging. In the 18th century, "gaffer" was a term of respect for old people, most likely derived from "godfather," and "fogy" was simply a word for a veteran; by the beginning of the 19th century both had become derisive words. Around the same time, "codger," "old guard" and "superannuated" acquired pejorative senses, joined later in the century by new disparagements like "oldster," "fuddy-duddy," "coot" and "geezer."

The historian David Hackett Fischer argued in "Growing Old in America" that those shifts reflected a dramatic change in society, as deference to the old was replaced by contempt and neglect. The difference is symbolized by a shift from the age-becoming fashions of the 18th century to the youthful ones of the early 19th century: powdered wigs and loose, full-cut coats and gowns yielded to diaphanous dresses for women and to toupees, tight trousers and high collars for men.

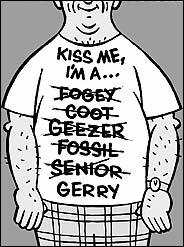

Age-disparaging words are the natural byproduct of a cult of youth, so it's not surprising that so many of them appeared in the Boomer Age. Since the 1950's, the language has added "dinosaur," "fossil," "blue-hair," "cotton-top," "gerry" and "trog," as well as flip terms for parents like "rents" and "p's." Gays speak of "trolls," who hang out in bars called "wrinkle rooms." And that's not to mention British imports like "wrinkly," "crinkly" and "crumbly," which together sound like a law firm out of "Bleak House."

The circumlocutions and euphemisms people use when speaking of the aged are equally revealing. The Victorians coined expressions like "of a mature age" and "70 years young," an expression first credited to Oliver Wendell Holmes. The 20th century brought "senior citizen," "golden ager" and "Third Age." The comparative "older" has become an absolute term, in a way that mirrors the development of "elderly" 350 years earlier - when somebody talks about "older Americans" nowadays, no one asks, "Older than whom?"

Granted, many of those phrases reflect a new perception of age as an important social issue. However fulsome "senior citizen" may sound, it's the first term to acknowledge the old as a political constituency. But most of these euphemisms are too forced for everyday conversation. And even in politics and business, they're often replaced with more oblique phraseology. Banks have abandoned "senior accounts" for "Classic checking," or "Renaissance checking," and airline programs for older fliers go by names like "Young at Heart" and "Silver Wings Travel Club." Euphemism is like waxing a floor - you have to keep reapplying new coats as the old ones yellow.

The condescension of our euphemisms and the impertinence of our slang both testify to our discomfort about confronting the facts of age head-on. As G. K. Chesterton remarked 80 years ago in his essay "The Prudery of Slang": "There was a time when it was customary to call a father a father. ... Now, it appears to be considered a mark of advanced intelligence to call your father a bean or a scream. It is obvious to me that calling the old gentleman 'father' is facing the facts of nature. It is also obvious that calling him 'bean' is merely weaving a graceful fairy tale to cover the facts of nature."

True, these facts of nature leave every Western society a bit ill at ease. The British, French and Germans talk about the old with the same mix of irreverence and euphemism as Americans. But only the United States makes youth an essential feature of its national self-conception. As C. Vann Woodward once put it, we see ourselves as "the eternal Peter Pan among nations."

The youthfulness of our generational language may make it even harder for us baby boomers to come to terms with our lengthening demographic shadow. Linguistically, though, we'll have to reap what we have sown. As Chesterton said of the young people of his own age, "As they have no defense against their fathers except a new fashion, they will have no defense against their sons except an old fashion."

Geoffrey Nunberg, a Stanford linguist, is heard on NPR's "Fresh Air" and is the author of the coming book "Going Nucular" (PublicAffairscq, 2004).

|

|