|

|

Insurers Reel From Spitzer's Strike

-Subpoena on Bid-Rigging Spurred Rush to Admit Collusion With Broker Fallout for a Family Dynasty-

By Monica Langley and Theo Francis, The Wall Street Journal

October 18, 2004

"It's the same kind of cartel-like behavior carried out by organized crime," Attorney General Eliot Spitzer privately told his top officials, according to people who heard the remarks. "It's like the Mafia's 'Cement Club,' " added Peter Pope, deputy attorney general in charge of the criminal division, at the same meeting. Mr. Pope was referring to construction projects in which a corrupt contractor rotated cement companies into jobs based on kickbacks.

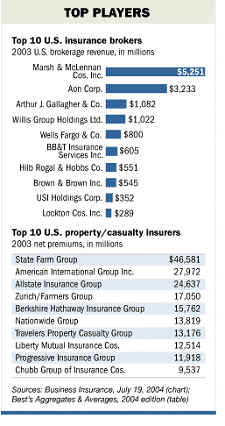

Mr. Spitzer's office last week charged that Marsh & McLennan Cos., the world's largest insurance broker, with as much as 20% of the market, played the part of the corrupt contractor. In a civil complaint filed Thursday in a New York state court, Mr. Spitzer alleged that New York-based Marsh cheated corporate clients by rigging bids and collecting big fees from major insurance companies for throwing business their way.

The charges followed a frantic two weeks in which major insurance companies, including American International Group Inc., Ace Ltd. and Hartford Financial Services Group Inc., scrambled to present evidence to Mr. Spitzer of how they worked with Marsh to cheat customers. By helping the attorney general build his case, the insurers were hoping to get credit for cooperation and reduce their eventual punishment. The result: a probe that might have dragged on for months rapidly accelerated.

Mr. Spitzer has secured guilty pleas from two midlevel managers at AIG and one Ace executive for their roles in the alleged scheme. More criminal cases against individuals are expected in coming weeks.

The broad nature of the bid-rigging allegations raises the possibility that the scandal could engulf other major players and lead to an overhaul of the insurance business. Marsh, AIG and Ace have suspended the practice of "contingent commissions," in which an insurer pays a broker in exchange for steering business its way.

Next on the hot seat: Aon Corp., the second-largest U.S. insurance broker, with more than $6.7 billion in brokerage revenue world-wide last year. Investigators are examining whether the Chicago-based firm improperly steered its customers based on fees from insurers and whether it engaged in bid-rigging. Mr. Spitzer is also probing whether Aon directed business to insurers willing to use its services when buying "reinsurance," or insurance coverage for insurance companies, according to people familiar with the matter. This practice, known as "tying" or "leveraging," might result in policyholders getting an inferior deal.

Aon said in a statement last week that soliciting fictitious quotes, bid-rigging and accepting payments from insurers in exchange for not shopping business around "would violate Aon policies." Aon said "to the best of our knowledge, our employees have not engaged" in those practices.

Aon also said it is cooperating with Mr. Spitzer's office. However, the head of the investment protection unit in Mr. Spitzer's office, David D. Brown IV, accused Aon of "dragging its feet as much as it can."

Mr. Spitzer's inquiry is widening. He plans to examine whether life and health insurers engaged in bid-rigging, according to people familiar with the matter. On Friday, two companies reported receiving fresh subpoenas from the attorney general: life insurer MetLife Inc. and National Financial Partners Corp., a broker to wealthy individuals and smaller companies. Both companies had received subpoenas earlier in the probe. A MetLife spokesman declined to comment. National Financial Partners said it isn't aware of its employees asking insurers to provide fictitious or inflated quotes to clients.

"Our investigation is reaching into many corners of the insurance industry to determine how corrupt its business practices are," said Mr. Spitzer in an interview.

Insurance stocks have plummeted and their market value has collectively fallen by tens of billions of dollars. Marsh stock has fallen by more than one-third; the company lost a total of $9 billion in market capitalization last Thursday and Friday.

For now, the hottest seat in the industry is occupied by Jeffrey W. Greenberg, Marsh's chairman and chief executive. At last Thursday's news conference announcing the case against Marsh, Mr. Spitzer snapped: "The leadership of that company is not a leadership I will talk to."

Mr. Greenberg is part of an insurance dynasty that has been shaken by Mr. Spitzer's charges. His brother runs Ace and his father runs AIG -- and both insurers were among the first to name Jeffrey Greenberg's company as a possible wrongdoer. Twice in the past year, Mr. Spitzer has found problems at Marsh units. Last fall, its Putnam Investments unit became the first mutual-fund company charged in that industry's trading scandal for allowing favored customers to buy and sell shares in ways that cheated other investors. Putnam settled charges against it for $110 million. And earlier this year, the firm's Mercer Human Resource Consulting unit admitted to giving the New York Stock Exchange's board inaccurate or incomplete information about the pay of former stock exchange Chairman Dick Grasso.

'Pay to Play'

At the heart of the insurance scandal are allegations of bid-rigging and "pay to play" deals. Businesses seeking insurance often hire a broker such as Marsh, which in turn solicits bids from several insurers. Marsh is alleged to have sought artificially high bids from some insurance companies so it could guarantee that the bid of a preferred insurer on a given deal would appear cheapest and would win the business at hand. Such machinations violate New York state antitrust laws and the broker's duty to act in the best interest of its clients, Mr. Spitzer charges.

The lawsuit also targets contingent commissions, the widespread practice among insurers of paying brokers extra commissions based on the volume or profitability of the business the broker directs to them. These commissions gave Marsh an incentive to direct business to insurers paying it the most-generous fees, not those with the best price or terms, Mr. Spitzer alleges.

It was the industry's use of contingent commissions that initially triggered Mr. Spitzer's investigation. In April, the attorney general issued subpoenas about the fees, which a growing number of policyholders and others have criticized as a kind of kickback.

Within a few months, hundreds of boxes of documents crowded the 23rd floor of the lower Manhattan skyscraper where the attorney general's investment protection bureau is located. Mr. Brown, the unit's head, instructed interns and law students to plow through them. They found many instances of Marsh brokers steering business to insurers paying the most in contingency commissions, according to a person familiar with the matter.

On Thursday, Sept. 9, Mr. Brown, riding the train back to Albany where his family lives, received an e-mail message on his BlackBerry from the office. The subject line read, "Just when you thought you had heard it all," he says. The message contained excerpts from one insurer's e-mail that described Marsh fixing insurance bids. Mr. Brown forwarded the e-mail to Mr. Spitzer, who answered, "These guys are in real trouble," according to a person familiar with the exchange.

Early the next week, an excited law student presented to Mr. Brown another apparent example of bid-rigging. On Sept. 17, a wave of subpoenas went out under the state law prohibiting fraud and under the Donnelly Act, New York's antitrust law. Insurance companies had two weeks to respond.

That's when the insurance industry went into a tizzy. The companies had retained outside lawyers with white-collar-crime expertise. For example, Marsh hired Davis Polk & Wardwell, a law firm whose team includes Carey Dunne, a Harvard Law School classmate of both Mr. Spitzer and Mr. Brown. (Mr. Dunne had recommended that Mr. Spitzer hire Mr. Brown for his current job.)

Among the first calls to the attorney general was one from AIG, headed by Maurice R. "Hank" Greenberg, whose eldest son is Jeffrey Greenberg, Marsh's chief executive. Another early call came from yet another insurance firm headed by a Greenberg -- Ace, whose president is Evan Greenberg, Jeffrey's younger brother.

Ace and AIG jockeyed to be the first to meet with the attorney general. "They were racing to be the first to acknowledge the bid-rigging," says one official. "They wanted to appear most cooperative to get the best treatment."

The insurance executives took Mr. Spitzer seriously because of his track record: His investigations of Wall Street brokerages' research practices and of the mutual-fund industry had exposed widespread and longstanding malfeasance. Both led to huge fines and an industry overhaul.

On Oct. 1, Mr. Spitzer's lawyers met in the morning with AIG and in the afternoon with Ace. Both insurers disclosed instances of alleged price-fixing by Marsh. Hanging over the room was the knowledge that companies headed by a father and a son were providing evidence that could damage another son.

Hartford officials visited the attorney general's staff the following week with Hartford's own evidence of purported bid-rigging. Mr. Spitzer's lawyers quickly added the new information to a draft complaint they were preparing.

It wasn't until last Tuesday that Marsh -- the central player in the alleged price-fixing scheme -- came in to address the bid-rigging charges. Marsh's general counsel, William Rosoff, said he knew of no wrongdoing, according to a person at the meeting. Mr. Rosoff said Mr. Spitzer's subpoenas were hurting Marsh's business, and then asked the attorney general to describe what his investigation had found, this person says.

The attorney general refused. "You've had every opportunity to figure this out for yourself," he told Mr. Rosoff, says this person. "You've had clear indications for the last six months."

Marsh declined to comment on Mr. Spitzer's allegations or its meetings with the attorney general's office. "I can only say that we take the allegations very seriously. Our company doesn't stand for the sorts of things that are alleged," Jeffrey Greenberg said in an interview last Friday. "We don't condone bid-rigging, we don't condone wrongdoing."

Around the same time, Mr. Spitzer's office told two mid-level AIG managers to cooperate or face arrest. Jean-Baptist Tateossian, a manager in AIG's national accounts unit, and Karen Radke, a senior vice president in an AIG unit, decided to plead guilty to a felony, which would be reduced to a misdemeanor in exchange for their cooperation. Lawyers for both Mr. Tateossian and Ms. Radke declined to comment.

With the pleas settled, the attorney general filed the complaint on Thursday. At the news conference afterward, he lambasted Marsh's management, and called on the company's board to make changes.

On Friday, AIG's Hank Greenberg held a conference call with research analysts and investors. He said he was "sickened" by the wrongdoing and said AIG was cooperating fully. Mr. Greenberg also looked to spread the blame around. He said New York's insurance regulator failed to respond to requests from AIG in July 2002 and October 2003 for clarification on the legality of the contingent-fee arrangements.

State Insurance Superintendent Gregory V. Serio said in an interview that instead of giving a quick answer to AIG, his department decided to find out more about commission practices. He said his department has sought information from hundreds of insurers and brokers, and its investigation is continuing.

The various probes highlight a weakness in the industry's regulation. Insurance is the only financial-services industry without a federal regulator, and the patchwork of state insurance regulators has long been viewed as weak.

When Hank Greenberg was asked on the conference call which broker's contingent-fee arrangements he had raised with the insurance department, he said simply, "Marsh." It was a dramatic moment because it meant he had fingered his son's company.

At an AIG management meeting on Saturday, a colleague asked Mr. Greenberg about the awkward situation. Mr. Greenberg told him, "Of course, I'm sad. He's my son," according to an AIG executive. Mr. Greenberg hasn't spoken with either son involved in the probe, an AIG spokesman says.

Within the industry, two burning questions are how high in the management ranks culpability will reach and how widespread the improper practices will prove to be.

AIG's Mr. Greenberg says his firm's internal probe, prompted by the subpoena the firm received in September from Mr. Spitzer's office, so far has found no link to senior management but is continuing. The two managers who pleaded guilty Thursday both worked for a division of AIG's American Home Assurance Co. The unit sells excess-casualty insurance -- coverage beyond a policyholder's regular accident insurance. Mr. Greenberg said both have been suspended.

Private lawsuits also are multiplying. Marsh, Aon and fellow broker Willis Group Holdings Inc. face a civil-racketeering suit filed in August by a policyholder, Opticare Healthy Systems Inc., Waterbury, Conn. The suit seeks class-action status in a federal court. Just after Mr. Spitzer's action last week, a policyholder group filed a civil suit in a California state court, alleging deceptive practices by a San Diego benefits broker and three major life and group-benefits insurers, MetLife, Prudential Financial and Cigna Corp.

I

nsurance executives are wondering if Marsh, which has promoted its strong service and commitment to clients, can maintain its dominance in the insurance-brokerage business. At Marsh, contingent commissions are a hefty chunk of revenue on top of the basic fees it receives for acting as a middleman to bring together buyers and sellers of insurance. The buyer usually pays the broker's basic fees, which can be either a flat sum or a percentage of the insurance premium.

Mr. Spitzer says contingent commissions totaled $800 million of Marsh's $11.5 billion in revenue last year. (Marsh had 2003 net income of $1.5 billion.) The fees are so profitable that Prudential Securities insurance analyst Jay Gelb estimates their absence is likely to put Marsh's 2005 earnings per share in the neighborhood of $2.25 instead of $3.45 as previously estimated.

Preferred Carriers

Marsh has maintained that it took care to prevent contingent-fee pacts from influencing its brokers' recommendations. But Mr. Spitzer's complaint identifies repeated instances in which managers purportedly pressured brokers to place business with certain insurers. Marsh managers, for instance, created lists of preferred insurance carriers, rewarded employees who sold more insurance from these companies and chastised those who didn't, the complaint says.

In April 2001, an unnamed Marsh managing director in one of the brokerage business's units wrote to regional heads and asked for "twenty accounts that you can move from an incumbent" insurer to one with a contingent-fee pact. On another occasion, an unidentified Marsh broker was praised by a boss for moving some policies to insurers who paid contingency fees to Marsh, the complaint says.

Beginning in about 2001, the complaint alleges, the effort to place business with preferred insurers had taken a big step: to bid-rigging. The complaint cites "a cast of the world's largest insurance companies" as participants.

It worked this way, according to the complaint: Marsh brokers would call underwriters at insurers including AIG and Ace for "B" quotes -- bids that wouldn't be good enough to win the business in question. In these cases, the underwriters knew that Marsh wanted another insurer to win the business.

Why participate? The insurance companies knew Marsh would protect their bids on other occasions, the complaint says. As one Marsh managing director put it to AIG: Marsh "protected AIG's a-," when AIG wanted to retain business, and it expected AIG to help Marsh "protect" others, according to the complaint. It doesn't say where the managing director made the remark.

In December 2002, Patricia Abrams, the Ace employee who pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor Friday, worsened the insurer's bid to provide excess casualty insurance to manufacturer Fortune Brands Inc., boosting the cost to $1.1 million from $990,000, according to the suit and a person familiar with the investigation. Ms. Abrams said in an e-mail to a higher-up the following day that Marsh "requested we increase premium to $1.1M to be less competitive, so AIG does not loose [sic] the business," according to the complaint. An attorney for Ms. Abrams, who has been suspended, declined to comment.

Evan Greenberg, Ace's president and CEO, called Mr. Spitzer's allegations "deeply concerning" in an open letter to employees on Sunday. If an internal investigation uncovers lapses, "they will be fixed -- quickly and permanently," he wrote.

"Fortune Brands works hard to keep insurance costs and all expenses as low as possible, so we're obviously concerned," says a spokesman for the Lincolnshire, Ill., maker of Jim Beam whisky and Titleist golf balls.

Sometimes, Marsh asked for what one insurer called "drive-bys" -- insurance-company personnel making a presentation at a meeting with a client to bolster a fake bid, according to the complaint. In 2001, Marsh asked Munich American Risk Partners, a unit of reinsurance giant Munich Re, to "send a 'live body' " so Marsh could "introduce competition" for a client, the lawsuit says.

Having received several such requests, the lawsuit says, a Munich American regional manager replied in an e-mail: "We don't have the staff to attend meetings just for the sake of being a 'body' ." Munich-American, of Princeton, N.J., has said it is cooperating with the attorney general's inquiry.

In several instances, AIG ended up with business it wasn't supposed to get, when the "A" bidder backed out at the last minute, according to the complaint. AIG hadn't completed the underwriting in those cases and had to "back fill" -- that is, prepare the necessary analysis after the fact.

In one case, an assistant vice president of underwriting at CNA Financial Corp. balked at providing a fake bid for insurance to cover workers' compensation and general liability for a $900 million project to renovate and build 70 schools in Greenville, S.C. According to the complaint, a Marsh broker asked the underwriter to provide a bid that would be "reasonably competitive, but will not be a winner."

In the absence of a bid from the CNA underwriter, Marsh "falsely submitted a bid under CNA's name," the complaint says. A spokesman for CNA declined to comment.

Mr. Spitzer has made clear he expects his probe to reach to employee benefits, life insurance and home and auto insurance. "Virtually every line of insurance has been implicated," he said last week.

For instance, last week's complaint alleges that Marsh had negotiated a $1 million "no shopping" agreement, under which the company would have recommended to its top individual clients who had personal insurance through \*Chubb Corp. that they renew those policies. The complaint said that pact, never consummated, would have been "a paid abdication of Marsh's duty to its clients."

Chubb said it is cooperating fully with the attorney general and isn't aware of any impending charges. Chubb also said it believes that neither the company nor its employees "violated any law or regulation governing compensation of insurance brokers and independent agents."

|

|