|

|

Interview with Babak Abbaszadeh, Médecins Sans Frontières Medical Doctor in Abkhazia, Georgia

April 2, 2004

Babak Abbaszadeh, MD, graduated from Tehran Azad Medical University in 1999. Since graduating, he has practiced medicine in locations with vulnerable civilians: at the Iran-Iraq border with a post conflict population, in Afghan refugee camps and until recently in Abkhazia, Georgia. He is 31 years old and married. After a short interlude at home in Iran, he and his wife left in April 2004 for his next posting in Ethiopia.

(GAA Intern Ekaterine Paresashvili edited the interview.)

Can you give us some of the details of your arrival in Georgia and in Abkhazia? When, where and how did you get there and what was your assignment?

I arrived in Georgia on 11th of January 2003 and spent almost 6 months in Tbilisi (capital city of Georgia) and Akhmeta (Eastern Georgia). Then I moved to Abkhazia where I stayed for 7 months until the end of January 2004. It was my second mission with MSF France and I was responsible for primary health care to a vulnerable population.

How did you understand the Georgian-Abkhazian armed conflict that had gone on in the area? How do you describe this conflict?

The armed conflict that took place almost ten years ago created two different situations.

First, it forced thousands of Georgian people to leave their homes in Abkhazia. Many had lost their family members, their jobs, their factories and businesses. Some of these Internally Displaced People settled down in Tbilisi. There they had to find new jobs or become self-employed to earn their living. The others moved to Zugdidi mainly, the town closest to the Abkhazian-Georgian border, where they live with their relatives. Many other people moved to Russia.

Secondly, the war devastated the entire Abkhazian infrastructure. The economic and social situation there is much worse than in other parts of Georgia. The people suffer from a number of problems that show up as psychological problems--major depression, anxiety disorders, etc. In the case of the many families that are half Georgian and half Abkhazian, the current situation is even more difficult for them.

Actually in MSF we don't pay attention to the political aspect of our work. We focus on ways to show international organizations the problems and the situation of the vulnerable population residing in Abkhazia.

Describe the general and unusual conditions that you observed.

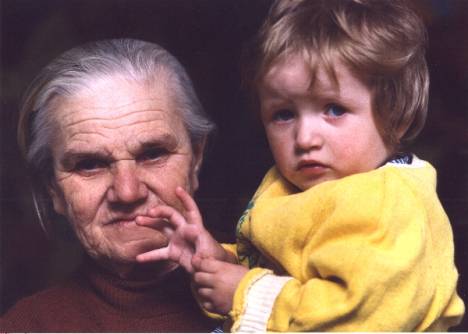

Unlike the MSF missions in other countries where we mainly face emergency and epidemic outbreaks, most (> 70%) of our patients in the Abkhazia, Georgia, were more than 65 years old. The most common diseases were Chronic Diseases as Hypertension (HTN), Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and Diabetes. Cancer was yet another major problem but we didn't have enough resources to treat it. I had quite a number of patients who were blind; one had an amputated leg; others had HTN and Cardiac Heart failure. Many lived alone waiting for their ICRC (International Committee of Red Cross) food once per day and our home visiting team that came every ten days.

What kind of aid did MSF Programs provide as part of the MSF Programs throughout Georgia?

MSF has one Primary Health Care Clinic (PHCC) in Tbilisi located in a poor district. There we identified almost 7, 000 vulnerable persons according to the following criteria:

· Old and single

· Families with many children (More than three children)

· Orphans

· Single mothers with children

· Families with no income

· Disabled people (Disability grade I and II)

· Refugees and IDPs

· Homeless people

We provide them with free medical health care, such as a medical consultation, nursing care. We arranged referrals for hospitalization, observation while they were hospitalized. We also provided health education.

In Abkhazia we had a much bigger mission than in other parts of Georgia. We provided drugs for 13 health facilities and we supported almost 20,000 vulnerable people all over Abkhazia. This effort was related to the Health Access Program. MSF also runs a National Tuberculosis program throughout Abkhazia.

What was the biggest issue facing older people in Abkhazia?

Being single and with no one to care for them. The elderly had problems with their normal activities of daily life (ADL), such as bathing, toileting, and answering telephones. Almost 20% of our beneficiaries were completely bedridden. We had a an ICRC social worker network who brought food once a day to bedridden patients in their homes and helped them with their daily activities. But in other parts of Georgia, namely in Tbilisi and Akhmeta, where MSF also runs programs, such a network does not exist.

Unfortunately, the Abkhazian social network could not meet all the needs of bedridden patients. The social workers had no formal training. They were old and single themselves. The only thing that made them different from their bedridden patients was their ability to walk. They could not perform at the same level or same standards as one would normally expect from a certified social worker. For example, most of them could not move or turn the patient with bedsores in their beds. Many could not distinguish between an emergency situation and a non-emergency situation. Some could not give drugs that we prescribed for the patient at a proper dosage and time. They were old themselves and sometimes forgot to manage the drug usage. So, we normally relied on patients themselves to use their drugs properly.

Oftentimes incapacitated patients (who had suffered from stroke with hemi paralysis) had to take the medications on their own. Let me give you an example: During one home visit, we found an old man with right side hemi paralysis (right hand and leg paralysis). He could hardly move or speak. I tried to find out how long he had suffered in this condition. He tried to answer me but I didn't understand a word. Then I brought a paper and a pen to the patient. Writing his answers with his left hand, we learned that he had had sleeping disorders for the last 4 years following his stroke. He could not sleep because he afraid of dying while sleeping. So, he would lie in front of the television during the whole night with the volume turned very high.

I examined him carefully. He was quite healthy and everything was OK except high blood pressure (210/110). I gave him "Atenolol" and instructed him to take it for 5 days. Then I told him that I would come back to monitor the dosage and check him again. We also gave him crutches to help him move more.

Returning after five days, I found out that his blood pressure was still high. I asked the reason and he showed the plastic bags with medications that I had given to him. (MSF has special plastic bags for the patients that are marked on how to use the drug, with illustrations of 'sun for morning and moon for night.' The bags have a special closure on top to prevent moisture and dust getting into the plastic bag). He had not touched the tablets at all because he could not open or close the plastic bags with his paralyzed mouth and hand. I felt completely stupid that I'd not thought about it before. So we put the drugs on a plate and covered it with another plate. Now he is OK and can also sleep well.

Do you remember how some older people were meeting some of their basic needs for shelter, fuel, clothing, bedding, household item, and mobility? (incapacity, population movement and transport, disability Family and social needs (separation, dependents, security, changes in social structures, loss of status Health care (services, food, water, sanitation, psychological needs) Economic and legal issues (income, information , documentation, skills training?)

I'll start with income. Most people were old, single with their monthly pension of around 30-40 rubles for income. (To compare, a loaf of bread costs 5 rubles). The pension did not meet their most basic needs. The ICRC supplied food once a day. Some received warm food but most got dry food on a monthly basis. Some older persons had helpful neighbors who cooked food for them. During the Soviet times, the Government had a centralized heating and water system maintained by the Soviet Government. However, after the political collapse, all these central systems also collapsed. Therefore, MSF faced a big problem in trying to provide utilities, including a heating system for bedridden persons.

Furthermore, most vulnerable people lived in old-- but huge--tall buildings without working elevators. Since the people were infirm, they couldn't move up and down the stairs. Naturally, old people with osteoporosis and kiphosis and heart failure could not climb the steps of a fifteen-story building. I had several patients who had not left their apartments for five to ten years; their neighbors took care of all their basic needs.

Looking at security issues, most older persons did not have much property to make them targets of potential robbery targets. However, I learned of several robberies even under these circumstances: Thieves robbed older people of pots, wooden chairs and even an out-of- order television. Bedridden patients would usually ask us to lock the door when we left until the next day when we or ICRC social workers would return. We had special places to hide the key that just the ICRC social worker and we knew.

Many of the elderly suffered from paralysis, heart failure, diabetic ulcer, leg edema, stroke and partial paralysis, osteoporosis and severe joint pain. More importantly, they faced depression as a result of losing their children in the war or after being alone for several years.

We tried to connect them to nearby neighbors so that they could help and support each other. We distributed a "walker" or walking frame, crutches and an inflatable pillow to try to help older persons a little bit. But it was not enough because they needed someone to walk them out every day--not just once a week.

How did you go about helping old people? How and in what circumstances were old people consulted?

For completely bedridden patients, we had a mobile team with one general physician and a nurse; they went to each home to visit everyday all over Sukhumi, the capital of Abkhazia. For those people who could move on their own, we had a network of clinics to provide them with free medicines, consultations and lab examinations. We tried to choose the clinics located as close as possible to the places of residence of the vulnerable population. In Sukhumi, most patients could go to the clinic on foot. However, in other provinces of Abkhazia, we just had one clinic. It was very difficult for vulnerable people to come to clinics if they lived in the peripheral villages due to travel expenses, i.e. 25-30 rubles, to travel to the main town. So, we had a mobile team visiting homes just once per week in these provinces.

How was assessment carried out?

We received monthly morbidity data on the vulnerable through our doctors, and we tried to keep current mortality data. Actually there was no reliable method of collecting accurate mortality data. We started to establish a system to register all the new and old cases that came to clinics or that mobile teams recorded so we could have correct morbidity and mortality data. It was difficult to overcome the challenge of the great geographical area that our activities tried to cover: We had thirteen clinics with different doctors who worked very distant from each other. Our easternmost clinic in Gali, east of Abkhazia, lay about 300 kilometers (186 miles) from our westernmost clinic in Gagra, west of Abkhazia. Our morbidity data was only approximate.

|

|

|