|

Surveying the Brain for Origins of the Senior Moment

By Robert Lee Hotz, The Wall Street Journal

December 2, 2008

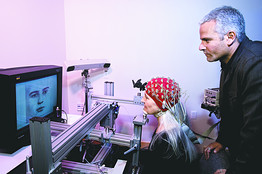

University of California, San Francisco neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley monitors the brain in an attempt to understand how age erodes concentration.

Aging Brings Mental Changes -- Including a Slowdown of Mere Milliseconds -- That Drive Us to Distraction.

Nyla Puccinelli sat patiently at the crossroads of memory, attention and aging, while a lab technician threaded color-coded electrodes into the mesh cap on her head. A retired school teacher, she'd always had trouble recalling her students' names but she worried more now about her memory and found it harder to shrug off distractions.

"If I am really concentrating on something now, I have to turn off the radio," Ms. Puccinelli, 69 years old, said. "There is a lack of concentration. Because you're getting older, you get more concerned about it."

By recording the electrical activity of her mind at work, neurologist Adam Gazzaley at the University of California at San Francisco was using her healthy brain as a road map of mental changes that age brings to us all. In particular, Dr. Gazzaley and his colleagues were trying to understand why aging drives us all to distraction.

At the slightest interruption -- an irritating ring tone, an insistent email alert or the hushed conversation in the adjacent office cubicle -- our thoughts can plunge into the mental underbrush like hounds snuffling after the wrong scent.

As scientists document the normal brain changes at fault, they are highlighting a growing conflict between the push-me-pull-you demands of modern multitasking and our waning powers of concentration. By one estimate, the average office worker is interrupted every three minutes. Indeed, our inability to ignore irrelevant intrusions as we grow older may arise from a basic breakdown of internal brain communications involving memory, attention span and mental focus starting in middle age, researchers have discovered.

These days, we look for any insight into how aging alters the brain. "My patients are most worried about having something go wrong with their brain as they age, more than they worry about cancer," says clinical neuropsychologist Karen Berman at the National Institute of Mental Health.

America's 78 million baby boomers are turning 60 at the rate of about 8,000 a day. By 2050, the world's population of those over 60 years old is expected to exceed the number of young people for the first time in history, according to the United Nations population division, with more than 2 billion people potentially prone to absent-minded moments of memory lapse and befuddlement.

"It is a public health issue -- the aging mind -- but more than that, it is an individual issue for so many people," says Dr. Gazzaley. "People don't want to retire. They want to compete in the workplace as well as they ever did, as well as the 20-year-old who was just hired in the room next to them. People want their brain to be the same their whole life."

No matter what we do, though, our brains normally shrink as we age -- a man's faster than a woman's -- affecting regions associated with learning and memory. Many genes linked to brain function in the prefrontal cortex also become less active, affecting how deftly we can orchestrate thoughts and actions.

By combining different measures of brain activity -- positron emission tomography, functional magnetic resonance imaging and electro-encephalography -- scientists for the first time can see how aging brain regions, designed to work in unison like the interlocking innards of an expensive watch, fail to mesh swiftly and smoothly. Normal aging, for example, disrupts the electrical crosstalk between major brain regions, researchers at Harvard University reported last December in the journal Neuron.

"With these new physiological techniques, we can look at what is going on the brain when you are supposed to be ignoring something," Dr. Gazzaley says.

Among the brain circuits that focus attention and memory, his research suggests, aging is a matter of milliseconds. In experiments testing how well people of different ages could recall faces and landscapes, Dr. Gazzaley and scientists at UC Berkeley found that among older people, the brain was slightly slower -- 200 milliseconds or so -- to ignore irrelevant test information. That instant of interference was enough to disrupt a memory in the making, they found.

"This is the distractibility," he says. In fact, it significantly affected how well older people did on memory tests compared to younger adults. "In that first fraction of a second, younger adults are much better at blocking things out," Dr. Gazzaley said.

During that momentary lapse, we can forget a new name, misplace our keys or lose our train of thought.

More Information on US Elder Rights Issues

Copyright © Global Action on Aging

Terms of Use |

Privacy Policy | Contact

Us

|