|

|

Preventable Disease Blinds Poor in Third World

By Celia W. Dugger, New York Times

Ethiopia

March 31, 2006

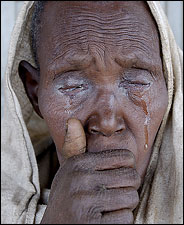

Mariella Furrer for The New York Times; Desta Ayanew, who lost her vision to the trachoma that plagued her for decades, kept her eyes closed because blinking was too painful. Ms. Ayanew, about 60, awaited an eye operation last year at a clinic in Alember, Ethiopia.

Mare Alehegn lay back nervously on the metal operating table, her heart visibly pounding beneath her sackcloth dress, and clenched her fists as the paramedic sliced into her eyelid. Repeated infections had scarred the undersides of her eyelids, causing them to contract and forcing her lashes in on her eyes. For years, each blink felt like thorns raking her eyeballs. She had plucked the hairs with crude tweezers, but the stubble grew back sharper still.

The scratching, for Mrs. Alehegn, 42, and millions worldwide, gradually clouds the eyeball, dimming vision and, if left untreated, eventually leads to a life shrouded in darkness. This is late-stage trachoma, a neglected disease of neglected people, and a preventable one, but for a lack of the modest resources that could defeat it.

This operation, which promised to lift the lashes off Mrs. Alehegn's lacerated eyes, is a 15-minute procedure so simple that a health worker with a few weeks of training can do it. The materials cost about $10.

The operation, performed last year, would not only deliver Mrs. Alehegn from disabling pain and stop the damage to her corneas, but it also would hold out hope of a new life for her daughter, Enatnesh, who waited vigilantly outside the operating room door at the free surgery camp here.

Mrs. Alehegn's husband left her years ago when the disease rendered her unable to do a wife's work. At 6, Enatnesh was forced to choose between a father who could support her, or a lifetime of hard labor to help a mother who had no one else to turn to.

"I chose my mother," said the frail, pigtailed slip of a girl, so ill fed that she looked closer to 10 than her current age, 16. "If I hadn't gone with her, she would have died. No one was there to even give her a glass of water."

Their tale is common among trachoma sufferers. Trachoma's blinding damage builds over decades of repeated infections that begin in babies. The infections are spread from person to person, or by hungry flies that feed from seeping eyes.

In large part because women look after the children, and children are the most heavily infected, women are three times more likely to get the blinding, late stage of the disease.

For many women, the pain and eventual blindness ensure a life of deepening destitution and dependency. They become a burden on daughters and granddaughters, making trachoma a generational scourge among women and girls who are often already the most vulnerable of the poor.

Trachoma disappeared from the United States and Europe as living standards improved, but remains endemic in much of Africa and parts of Latin America and Asia, its last, stubborn redoubts. The World Health Organization estimates that 70 million people are infected with it. Five million suffer from its late stages.

And two million are blind because of it.

A million people like Mrs. Alehegn need the eyelid surgery in Ethiopia alone. Yet last year only 60,000 got it, all paid for by nonprofit groups like the Carter Center, Orbis and Christian Blind Mission International.

As prevalent as trachoma remains, the W.H.O. has made the blinding late stage of the disease a target for eradication within a generation because, in theory at least, everything needed to vanquish it is available. Controlling trachoma depends on relatively simple advances in hygiene, antibiotics and the inexpensive operation that was performed on Mrs. Alehegn.

But the extent of the disease far exceeds the money and medical workers available. In poor countries like this one, faced with epidemics of AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, a disease like trachoma, which disables and blinds, has difficulty competing with those big killers.

Dr. Abebe Eshetu, a health official here in Ethiopia's Amhara region, described the resources available for trachoma as "a cup of water in the ocean."

Nowhere is the need greater than across this harsh rural landscape.

As dawn broke one day last year, hundreds of people desperate for relief streamed into an eyelid surgery camp run by the government and paid for by the Carter Center. Some of the oldest had walked days on feet twisted by arthritis to get here.

The throng spread across the scrubby land around a small health clinic. They wrapped shawls around their heads to shield themselves from sun and dust, made all the more agonizing by their affliction. Their cheeks were etched with the salty tracks of tears.

'Hair in the Eye'

Typical of those was Mrs. Alehegn, led stumbling and barefoot through stony fields by Enatnesh, who worriedly shielded her mother under a faded black umbrella.

As they waited their turn, Mrs. Alehegn explained that her troubles began more than 15 years ago when she developed "hair in the eye," as trachoma is known here. The pain made it impossible for her to cook over smoky dung fires, hike to distant wells for water or work in dusty fields, the essential duties of a wife.

Gradually the affliction soured her relationship with her husband, Asmare Demissie, who divorced her a decade ago, so he could marry a healthy woman.

"When I stopped getting up in the morning to do the housecleaning, when I stopped helping with the farm work, we started fighting," Mrs. Alehegn said.

The operation she had come for is still exceedingly rare in Ethiopia. Only 76 ophthalmologists practice in this vast nation of 70 million people. Most work in the capital, Addis Ababa, not in the rural areas where trachoma reigns.

Because of the extreme doctor shortage, nonprofit groups have paid for the training of ordinary government health workers over two to four weeks to do the eyelid surgery. The Carter Center, which favors a month of training, estimates the cost at $600 per worker, plus $800 for two surgical instrument kits for each of them.

Those trained make an incision that runs the length of the eyelid's underside, through the cartilagelike plate, then lift the side of the lid fringed with the eyelashes outward. Then they stitch the two sides back together. The patient is given a local anesthetic.

The operation cannot undo the damage already done to corneas, which makes the abraded eyes vulnerable to infections. But it can stop further injury. And because the disease often takes decades to render its victims blind, the operation can save a woman's sight and halt disabling pain.

For Mrs. Alehegn, the surgery was her second. Her plight is typical, for trachoma is both a disease of poverty and a disease that causes poverty.

After separating from her husband, she, Enatnesh and another daughter, Adelogne, then just 4, moved to a small, poor piece of land belonging to Mrs. Alehegn's family. About a year later, Mrs. Alehegn scraped together enough money for her first eyelid surgery. But as she aged, the underside of her eyelids — scarred by past trachoma infections — continued to shrink, turning her lashes inward again.

In recent years, her poverty was so dire she could not afford to have the surgery again. Her only income was the dollar or so a week that Enatnesh collected when she went to market to sell the cotton fabric her mother wove.

They were so poor they could not afford even 15 cents for soap.

"If I get my health back, it means everything," Mrs. Alehegn said. "I'll be able to work and support my family."

The others who journeyed to the camp told many such stories of hardship. In a land where early death is commonplace, some of those with the disease see their wounded eyes, ceaselessly leaking tears, as a kind of stigmata of sorrow.

Banchiayehu Gonete, an elderly widow, said three of her eight children had died young. The bitterest loss was of her eldest daughter, carried off by malaria at 40 with a baby still inside her. It was this daughter who had plucked her in-turned lashes, cooked for her and kept her company.

"God killed my children," said Mrs. Gonete, old and wrinkled, but unsure of her age. "I feel this pain as part of my mourning."

Nearby, Tsehainesh Beryihun, 10, sat with her grandmother, Yamrot Mekonen. Trachoma ended the girl's childhood years ago.

When her parents divorced, her mother gave Tsehainesh, then just a baby, to her paternal grandmother. As the old woman's sight failed, Tsehainesh became her servant. Since she was 7, she has fetched water, cooked, cleaned, collected dung and wood for the fire and swept the dirt floors, her grandmother said.

The girl sees her half brothers and sisters, the children of her father's second marriage, happily dashing to school, while she lives apart, her days filled with the grinding work of tending to a sickly, demanding old woman.

Her grandmother explained that the girl owes her. "I've supported her this far," Mrs. Mekonen said impassively, "so now it's her turn to support me."

Tsehainesh wept bitterly as her grandmother spoke, refusing to utter a word.

Ending Disability and Dependency

To break this cycle of debilitation and dependency, the goal is not eradication of the eye infections themselves, which most agree is neither practical nor necessary, but rather to reduce their frequency and intensity, a more achievable goal. This would avoid development of the devastating late stage of trachoma, called trichiasis, that makes surgery the sufferers' only salvation.

Toward that end, the World Health Organization has approved a strategy known as SAFE, an acronym that stands for surgery, antibiotics, face washing and environmental change, notably improved access to latrines and water.

Already, some researchers say, the growing use of antibiotics around the world to treat infections, even those unrelated to trachoma, has probably contributed to trachoma's decline. That is true even in very poor countries where there is no organized effort to tackle the disease, like Nepal and Malawi, they say.

The use of Zithromax, an antibiotic manufactured by Pfizer, has proved a breakthrough. The most common alternative is a cheap, messy antibiotic ointment that has to be applied twice daily to the eyes for six weeks. Zithromax, in contrast, can be taken in a single dose — making compliance easier and distribution to millions simpler.

By 2008, Pfizer, the world's largest drug maker, will have donated 145 million doses for trachoma control. Its contribution is administered by the International Trachoma Initiative, a nonprofit group. The drug has been provided in 11 of the 55 countries where trachoma remains a problem.

But globally, the World Health Organization estimates that at least 350 million people need the antibiotics once a year for three years to bring infection rates under control.

That equals more than a billion doses of azithromycin, the generic name for Zithromax. Trachoma is so rampant here in Ethiopia that an estimated 60 million people, or 86 percent of the country's population, need the drug.

Pfizer has not officially announced any additional donations, but Dr. Joseph M. Feczko, a Pfizer vice president, says the company will provide whatever is needed. "There's no cap or limit on this," he said. "We're in it for the long haul."

But even free drugs cost money to distribute. No global estimates are available for carrying out the SAFE strategy for trachoma control, but the Ethiopian government, beset by competing social problems, would have to come up with $30 million to reach even half the people who need the antibiotic, and $20 million more for public education on basic hygiene.

For now, the aim here is a more modest effort at localized control, but even that will not be easy.

An Ancient Scourge

Chlamydia trachomatis, the microorganism that causes trachoma, has been a source of misery for millennia, thriving in poor, crowded and unsanitary conditions. In ancient Egypt, in-turned eyelashes were plucked, then treated with a mixture of frankincense, lizard dung and donkey blood. In Victorian England, infected children were isolated in separate schools.

At the turn of the century, doctors at Ellis Island used a buttonhook to examine the undersides of immigrants' eyelids. Those with signs of trachoma were often shipped back to their home countries.

Swarming Musca sorbens flies play an ignominious role in spreading the disease. They crave eye discharge and pick up chlamydia as they burrow greedily, maddeningly into infected eyes.

"They cluster shoulder to shoulder around an infected eye," said Paul Emerson, the entomologist who did pioneering work on the role of the flies in spreading trachoma and who now runs the Carter Center's trachoma control program.

So inescapable, so persistent are they here in the Amhara region that children learn not to bother shooing them away. Even at the surgery camp, flies buzzed through the chicken wire that covered the windows of cramped operating rooms, harassing trachoma victims at the moment they sought relief.

Once the eggs of a female fly are ripe, she lays them in her preferred breeding medium, human feces, plentiful because most people here go to the bathroom outdoors.

But the flies cannot breed in simple, inexpensive pit latrines, Mr. Emerson said. He said he does not yet know why, but he thinks that a competing species that does thrive in latrines may eat the Musca sorbens maggots.

Ethiopia is now making a national effort to get people to build latrines, training thousands of village health workers to spread the word. It is also teaching children the importance of face washing in school.

But soap and water are scarce, too. Women often walk hours a day to wells to carry home precious pots of water balanced on their heads. And soap is a luxury for the poorest of the poor.

For those like Mrs. Alehegn, with late stage trachoma, surgery will continue to be necessary.

When her operation was complete, the health worker who performed it, Mola Dessie, pressed white cotton pads on Mrs. Alehegn's eyes to soak up the blood and applied antibiotic ointment to prevent infection. Then he covered her eyes with bandages.

Enatnesh wrapped her mother's head in a dingy cloth and slipped her stick-thin arm around her mother's waist to lead her away.

Mrs. Alehegn, who is illiterate, says she hopes that once she heals she will be able to weave more cloth, earn more money and do the domestic chores, leaving Enatnesh freer to pursue an education. "I don't want her to live my life," she said.

Despite her dependence on her daughter, Mrs. Alehegn has allowed the girl to go to school. Enatnesh, though having fallen behind, is a diligent fifth grader at age 16, who proudly said she is ranked 5th out of 74 students in her class. She dreams of being a doctor.

Two days after her mother's surgery, Enatnesh led the way to her father's sturdily built hut a couple of hours walk away. There, as his second wife swept the compound and Enatnesh's 9-year-old half-brother sat in the shade, Mr. Demissie, 58, offered a regretful explanation for his decision to divorce his first wife.

He, too, had developed "hair in the eye," he said. And like his wife, he, too, had been forced to stop working. If they had not separated, he reckoned, they would both have died. Finally, Mr. Demissie decided to save himself.

His sick wife would never find anyone else to marry, he realized. But for him, a new, hardworking wife would provide a second chance. And after his marriage, he got the surgery to prevent his own blindness.

"If we had not been sick," he said sadly, "we would have raised our children together."

As he spoke, Enatnesh listened sorrowfully, her hand cupped over her mouth, her head bent low.

|

|