|

|

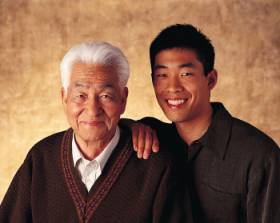

Taking Care of Elders Part of Culture

for Many

By Tanya Bricking, Honolulu Advertiser

February 28, 2005

Kaydi Fukunaga's 96-year-old father no longer knows she's his daughter.

The elderly man, who suffers from dementia, lets her take him on daily outings and allows her to help him make the best of life.

But he's unaware of the details: the way she monitors him from a camera she has mounted in his downstairs unit of their house, and the way she worries about becoming a burden to her own children.

The Palolo Valley woman attended yesterday's forum, "Okage Sama De: Challenges, Sacrifice and Satisfaction in Elder Care in Hawaii's

Japanese-American Community" at the Japanese Cultural Center because she was looking for a little support.

For her, it was uplifting to see almost 150 people at the forum, a panel discussion that touched on pressures facing families such as hers. She found comfort in the faces she saw and the message she heard.

"It's not only me," she said. "It's the culture. We take it as a responsibility, not an obligation, but a responsibility."

In a spiritual sense, "Okage Sama De" is Japanese for "thanks be to God," or "because of you," explained panelist Cullen Hayashida, an educator and long-term care researcher who co-hosts "Kupuna Connections," an 'Olelo TV program for seniors and caregivers.

The phrase - and theme of the panel discussion - implies commitment and cultural values, he said, and a sense that "because of you, I am blessed."

Such is the basis of the intergenerational support and focus on community held by many Japanese-Americans when it comes to families taking care of their own, he said.

It's not just a Japanese idea. Across the United States, families of Asian, black and Latino heritage rank among the highest in numbers of caregivers who take responsibility for the increasing needs of their elders within the family.

In Hawaii, outside help for such families slowly has grown through organizations such as Project Dana, a caregivers' support group that grew out of the Buddhist community in Mo'ili'ili and now has about 700 volunteers.

Jane Ifuku, a 65-year-old Mo'ili'ili resident, and her sister share responsibility for taking care of their 88-year-old mother.

Ifuku acknowledges the energy it takes to care for an aging relative when she and her sister are aging themselves. So she's willing to accept help. But she wants the younger generation to step up by volunteering to drive people to their appointments, prepare meals or do chores. Otherwise, she doesn't know what kind of help will be around when she is the one in need.

"I'm so busy thinking about my mother," she said. "I don't have time to think about my own needs."

A legislative issue

Hawaii's Legislature is aware of the needs of the aging community and is examining a long-term healthcare initiative, said Rep. Marilyn Lee, D-38th (Mililani, Mililani Mauka). Lawmakers also are considering giving qualified caregivers a $500 tax reimbursement, she said.

The best way to get bills that would help aging families passed is for people to make their opinions heard by calling their legislators, Lee said.

Sue Akau-Naki

Sue Akau-Naki, a Manoa woman who expects to be caring for her mother within the next 10 years, said the first step is to educate herself about the issues she's about to face.

Akau-Naki, who's half Japanese and a blend of Hawaiian, Chinese and Caucasian, said she reflects the rest of society in Hawaii: This isn't just an issue facing one demographic segment. Aging affects everyone.

Caregivers not alone

Somewhere between one in five and one in seven people in Hawaii provide assistance for their aging relatives, said panelist Karen Miyake, the county executive on aging for Honolulu's Elderly Affairs Division.

In Hawai'i, those 65 and older are expected to make up more than 18 percent of the population by 2020. And the number of frail elders who are 85 and older could quadruple over the next 50 years.

Older people, for the most part, are fiercely independent and don't want to ask for help, she said, but it's becoming more acceptable for families to talk about what they want to happen as they age.

One advantage the Japanese-American community has is that the whole family often shares in the burden of caring for an aging family member, she said.

Kaydi Fukunaga

Fukunaga, the woman caring for her 96-year-old father, said the first thing she did when her father got ill was to buy long-term healthcare insurance for herself.

She updates her living will and trust regularly. And even though her son says he'll take care of her when she grows old, she realizes she must have a plan she can live with without feeling as if she's anyone's obligation.

"They should do more of this," she said of yesterday's seminar. "It's uplifting to know I'm not alone."

A panel discussion on the issues involved in elder care drew almost 150 people to the Japanese Cultural Center yesterday.

Deborah Booker . The Honolulu Advertiser

|

|