|

Seniors Rise in Work Force After

Slump

Joseph

De Avila, Wall Street Journal

March 25, 2012

After

the recession thinned the ranks of

employed New Yorkers, one group has emerged

from the downturn with improved standing

in the labor force—older workers.

One in five working New Yorkers

is now 55 years or older, according to

the latest figures from the U.S. Census

Bureau, a sign of both the aging of the

baby boom generation and of older

workers holding on to jobs longer in the

face of savings diminished by the

recession.

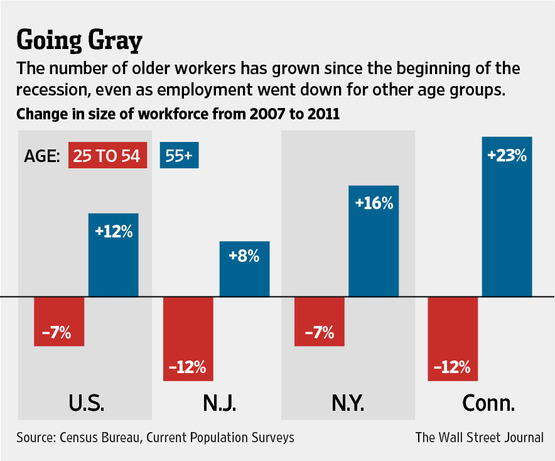

While young and middle-aged

workers in New York may still be

struggling to find work after the 2008

recession, older workers are becoming a

larger part of the work force,

increasing by 16% since 2007, according

to the Census. At the same time, working

New Yorkers between 25 and 54 declined

by 7%.

States across the country, including

neighboring New Jersey and Connecticut,

have experienced similar trends, as

older workers become more educated, stay

healthier and work later into life.

"The numbers will continue to go up,

particularly as more boomers hit their

60s," said Sara Rix, senior strategic

policy adviser with AARP Public Policy

Institute.

Baby boomers—generally defined as those

who were born between 1946 and 1964—now

make up about a quarter of the

population, both nationwide and in New

York. By 2030, nearly one in four New

Yorkers will be 60 years old or older,

said John Cochran, assistant director of

the New York state Office for the Aging.

To be sure, the past four years have

been painful for many older workers.

While the unemployment rate for people

older than 55 is 5.9% nationally—it is

8.3% overall—they often have a tougher

time finding jobs once they are

unemployed, taking about 54 weeks to get

a new job compared with 36 weeks for

younger workers, according to the Bureau

of Labor Statistics.

The recession also drained the savings

of many older workers, forcing them to

delay retirement.

"Certainly the economic downturn has

created a lot of pressure for people,"

said Marcie Pitt-Catsouphes, director of

the Sloan Center on Aging and Work at

Boston College.

In some cases, older New Yorkers like

Susan Stone, of Ossining, N.Y., in

Westchester County, may never retire.

Ms. Stone, who said she is in her 60s,

was laid off in 2009 from a job as a

speech pathologist. She has been working

part-time for about a year doing

strategic planning and marketing for a

nonprofit that helps senior citizens in

Manhattan.

Ms. Stone got her current job through

ReServe Inc., a group that connects

older workers to the nonprofit industry.

But she only works 14 hours a week and

scrapes by to pay her condo mortgage.

"The bottom line is that it's an

impossibility for me to retire,

especially now that I haven't been able

to build up income for the last three

years alone," said Ms. Stone, who is

looking for additional consulting work.

"I'm eating up whatever savings I had,

which was never significantly high.

Social Security certainly is not the

answer."

Older workers began growing in number

during the late 1980s and 90s, said Ms.

Rix, as the employers began switching

from pension retirement plans to 401(k)

accounts, which put more of the savings

burden on employees. Changes to Social

Security have encouraged older people to

continue working by offering larger

payments for retiring after the age of

70. And the trend is also fueled by

better physical health habits and more

white-collar jobs that don't take the

same toll as manual labor.

"More people are in the types of jobs

that facilitate a later working life,"

Ms. Rix said.

Older workers are a growing sections of

the work force even as they remain the

least educated, according to the Census.

About 20% of people 65 and older have

college degrees, and government

officials such as Mr. Cochran say that

boosting those numbers to help them

compete with better educated young

people will be the biggest challenge

confronting older workers.

"Are those skills still applicable and

are you ready to compete?" Mr. Cochran

said.

Meanwhile, employers are offering more

job training as employees get older,

said Ms. Pitt-Catsouphes of the Sloan

Center on Aging and Work. After the

recession, "no one wants to get caught

off guard and say, 'My skills are out of

date,'" she said.

Many workers have decided to use their

current skill set for as long as

possible.

Jennie Lyons, 65, wants to be able to

say she has been teaching for at least

20 years before she retires. That means

Ms. Lyons, from Tarrytown, N.Y., will

continue teaching computer science at a

private school in Westchester until she

is at least 69.

"I think it's going to take me saying,

'I'm done teaching,'" Ms. Lyons said.

"And I'm not done teaching yet."

Working those additional years will also

help her add to her savings before she

finally calls it quits, Ms. Lyons said.

"The longer I work, the easier it will

be to retire."

Others like Marcia Rose Yawitz, a

commercial real-estate broker, say they

never think about quitting even though

they can afford to retire comfortably.

Her competitive side won't let her do

it, she said. "It's just not in the

genes," says Ms. Yawitz, 77, from the

Upper West Side. "They say they are

going to have to carry me out of here."

|