|

|

To Be Elderly Is to Be Overlooked

as India Distributes Tsunami Relief

By Pia Sarkar, San Francisco Chronicle

India

February 10, 2005

Anjuvam Kaliappu, 90, was rescued from the tsunami by being passed from one grandson to another until reaching high ground.

Photo by R. Chandru, special to the Chronicle.

Anjammal spends her days in an old-age home, wondering where her family is or if they are even alive.

"I'm worried because they haven't gotten in touch with me," said Anjammal, a small, toothless 60-year-old woman in Manal Medu, a village in India's tsunami-ravaged Tamil Nadu state.

She never saw the ocean coming. All she saw was a flood of people running frantically from the shore, so she ran as well. Now, too afraid to return to her village by herself, she sits and waits, hoping her family will come and find her.

Anjammal, who uses only one name, is one of hundreds of elderly tsunami survivors in India who have been pushed to the limit of their endurance in the last stage of their lives. Like the children swept up by the tsunami, they were especially vulnerable. But unlike the children, who are considered the nation's future, the elderly have been cast off as a low priority in the tsunami's aftermath, some aid workers say.

HelpAge India, a voluntary organization based in New Delhi that works with the country's older citizens, estimates that the elderly accounted for nearly 30 percent of the tsunami victims in India, where more than 10,700 died and 5,640 are still missing.

Another 500,000 to 600,000 elderly were affected by the disaster, losing everything from family members to homes to livelihoods. Many older people have been forced to become primary caregivers for grandchildren after their own children were killed by the tsunami.

Indrani Rajadurai, director of HelpAge India's southern regional office in Madras, also known as Chennai, said her organization has provided relief packages for 6,200 family members, 90 percent of whom are elderly people.

"We felt that in any relief operation, it is the elders who are not getting their share," she said.

Much of India's aging population existed in grim conditions even before the tsunami. About 30 percent of the country's elderly live below the poverty line, according to HelpAge India. An estimated 80 percent live in rural areas, and 73 percent are illiterate. The life expectancy for an average Indian is 62 years, compared to 77 years for a Californian.

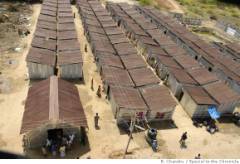

Pappathi Velayiran, 55, lives in one of 300 temporary structures constructed in the village of Nambiar Nagar in Nagapattinam, the area on the eastward bulge in the southern tip of India that was hit hardest by the tsunami.

"I don't like living here, but all my people are living here, so what shall I do alone?" said Velayiran, whose husband, son and daughter-in-law also live in the shelter.

Velayiran's village lost 270 people. She saved herself by clinging to a tree.

When the waves surged inland, she was hit in the back by another tree and is still in pain, she says. Her vision has been blurred by salt water damage to her eyes.

"What I'm wearing is all I have," she said, tugging on her tattered sari.

The elderly say they don't want special treatment because they are old. They just want help getting back on their feet.

Vellikannan Chakarapillai, 60, needs assistance rebuilding the shop where she sold fruits and snacks.

"Like everybody else, I have fear," said Chakarapillai, who is blind in her right eye. "Since everything is gone, I don't know what to do anymore. All we have is this temporary shelter."

Ninety-year-old Anjuvam Kaliappu sits on the ground outside a corrugated metal shelter in Naagur Ariyanattu Melatheru, a village in Nagapattinam, snatching what little shade she can from the shelter's slight overhang.

The shelters are made of corrugated metal that turns scorching hot in the midday sun.

"It burns so much, so we have to sit outside," Kaliappu said.

Kaliappu, who lives in the village along with 102 families, was rescued from the tsunami by her grandsons, who handed her off from one to another until she reached higher ground.

She plans to remain in the shelter rather than go to an old-age home. "I'd rather live with the people I gave birth to," she said.

As she spoke, a group of younger, stronger tsunami survivors wondered aloud why anyone would bother to speak to the elderly when they were going to die soon anyway.

At the old-age home in Manal Medu, Anjammal keeps herself busy by helping out the other residents, mainly to keep herself from constantly wondering about her family's fate.

Fifteen other elderly people came to the old-age home right after the tsunami, but their families have since reclaimed them. Anjammal is the only one left.

"I know someday they'll come and take me," she said. "Until then, I'll be here."

Refugees bake in the sun in Naagur Ariyanattu Melatheru, a village in Nagapattinam,

the region hardest hit by the tsunami in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

Photo by R. Chandru, special to the Chronicle

Vellikannan Chakarapillai lost the small shop where she sold snacks.

She needs help rebuilding.

Photo by R. Chandru, special to the Chronicle

Anjammal sits in an old-age home wondering when her family will get her

-- if they survived.

Photo by R. Chandru, special to the Chronicle

|

|