|

|

Asian Elder Care Faces New Dilemma

By Ann Graham Walker, New Zealand

May 31, 2005

The resource demands posed by aging baby boomers are well-known in Western countries. Less well-known is the fact that Eastern societies face a similar challenge.

At the recent annual meeting of the International Psychogeriatric Association held here, speakers from Asian countries described their efforts over the past few years to build services pretty much from scratch.

Their new approach is deeply foreign to Asian cultures, where the elderly are long valued; where it has been traditional for aging parents to live with their children. Age-related challenges like dementia have not been identified as a public health issue and instead have been hidden in families. The break in that pattern has been rapid and the need for care is urgent.

"I think the whole concept of the Asian family is changing before our very eyes," said Dr. L.L. Ng, a delegate at the conference who is head of the psychiatry department at Changi General Hospital in Singapore.

Canada's aging population is made mostly of baby boomers, who represented a sharp rise in the birth rate in the 1940s and '50s, but Asian countries are aging because their birth rates have dropped. People are living longer, middle classes are emerging. Similar to Westerners, Asians now in their 30s and 40s are a "sandwich generation," torn between caring for their parents, educating their children and making a living.

"Nowadays it is not surprising to hear of Malays sending their parents to an elderly home. That would not have happened 10 years ago but things are changing rapidly, and there is enormous pressure on our government to provide services," said Dr. Yusoff Suraya, a delegate from Malaysia.

Effect of emigration

Dr. Siwah Li, a psychiatrist from Hong Kong, pointed to another factor that is making things difficult for families in Asia. "Sometimes, even in a large family, there might be just one available to look after the parents. The others have emigrated to Canada or England or New Zealand."

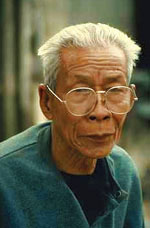

Dr. Li trained as a psychiatrist in England and has worked in New Zealand, but he returned to Hong Kong in 1994 to develop psychiatric services for the health department. The department wanted Dr. Li to take charge of two designated hospital wards.

"I said, 'No, no, that's not what I want. My aim is to develop community-based services.' It's not enough to look after the 200 patients in our two hospital wards. The work we have to do is much larger than that."

Dr. Byoung Hoon Oh, a psychiatry professor at Yonsei University in South Korea, described the challenges his country faces. South Korea has a population of 48 million, with 8.3% already over the age of 65 and a projected increase to 14% by 2018. "Eight per cent of people in the country's social service facilities are suffering from dementia," Dr. Oh said.

He is working hard to build psychogeriatric expertise in his department but it is an uphill battle because getting doctors in his country interested in psychiatry, particularly geriatric psychiatry, is not easy.

Asian delegates to this conference agreed age-related psychiatric issues tend to be shunned by psychiatrists and general practitioners alike in their region. Establishing services that are specialized, yet well-integrated with primary care, is a huge task.

Dr. Yung-Jen Yang is a psychiatrist at Tsao-Tun Psychiatric Centre in Nan-Tou, Taiwan, a country of 35 million where psychogeriatric facilities are limited and 9.5% of the population is already older than 65.

He is very proud of having helped to establish the Taiwanese Geriatric Psychiatry Association, formalized in March.

"The new era of geriatric psychiatry in Taiwan has begun," Dr. Yang told delegates.

Members of this group have published 62 articles in international journals.

Changing the way a society deals with its aging population in such a short time has required widescale borrowing and adaptation of Western models and recruitment of foreign consultants. This is happening at every level.

Adapting Western templates

But Western templates are a tool Asia needs to apply carefully. Care models are being reshaped and resized to fit local cultural sensitivities. In the Philippines, for example, the mini mental state exam has had to be translated into eight different languages.

Even simple, everyday management of demented people in a day-care centre presents challenges in countries where many languages and cultures co-exist, and the concept of elderly care services is novel. Singapore's Dr. Ng illustrated this point with a story about elderly mahjong players in her community.

Mahjong gambling is the major occupational intervention in Singapore seniors' day-care centres, she explained, because they come from a generation that has worked constantly and never developed hobbies. Surrounded by frail, demented-and occasionally fierce-mahjong players, staffers must tread carefully.

"If you are Cantonese and playing mahjong, and a foreign-trained staff member taps you on the shoulder and says, 'Hello', it is catastrophic," said Dr. Ng.

"According to Cantonese custom, this is very bad luck! I am Chinese, but I am not Cantonese, so even I didn't know this until I started working with dementia (patients)."

|

|