|

|

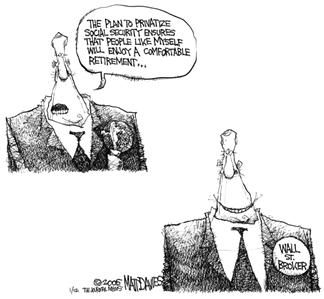

Social (in)Security on Wall St.

- Firms shy to openly back Bush plan -

By Tom Petruno and Walter Hamilton, Los Angeles Times

January 23, 2005

Matt Davies

Charles Schwab, the pioneer in discount stock trading, long has supported the idea of diverting a share of Social Security taxes into private investment accounts.

Schwab endorsed a book about the subject in 1999. His San Francisco-based company is helping to fund a group that is lobbying Congress for private accounts. He also has written newspaper op-ed pieces calling for more retirement savings options that would "reduce the dependence on government assistance."

With the debate about Social Security's future now kicking into high gear, the 67-year-old Schwab is staying out of the public eye.

"He has made a specific decision" to decline interview requests about the topic, a spokesman said.

Schwab's reticence is emblematic of the peculiar wallflower role adopted by much of the U.S. financial-services industry when it comes to overhauling Social Security.

The nation's brokerages and mutual-fund companies could be big winners if the government were to allow Americans to funnel some of their Social Security taxes into private investment accounts each year.

Companies such as Fidelity Investments, Vanguard Group, Merrill Lynch & Co. and Schwab collectively could reap billions of dollars in management fees and commissions in the long term.

Still, the emotions triggered by President Bush's call for restructuring Social Security have raised the risk that the financial industry could become a target of public ire.

Bush has touted the accounts as a way for Americans to earn returns over time that would give them greater retirement income than Social Security can promise. Workers most likely would give up their right to a portion of their future Social Security benefits by choosing private accounts.

Powerful groups, including the AFL-CIO and AARP, have bashed the idea of privatization, saying it would shred the retirement safety net and leave more Americans at the mercy of market swings.

The AFL-CIO in December sent letters to 46 major financial companies, asking them to renounce the concept of private Social Security accounts.

Facing that kind of reaction, "Most people in the (investment) business are keeping a very low profile," said Greg Valliere, chief strategist at Stanford Washington Research Group, a political-consulting firm. "They don't want to be identified as proponents, because of the potential backlash."

Among Wall Street's largest firms - Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Citigroup Inc. and Prudential Financial Inc. - all declined to comment about the Social Security debate.

Several financial-industry leaders say the official silence in part reflects that the Bush administration hasn't yet made a formal proposal for private accounts. Bush has raised the issue in general terms, saying that workers should be able to divert some percentage of their Social Security payroll taxes into accounts that could invest in stocks and bonds.

Worth the effort?

Individual contributions to these private accounts would be limited to $1,000 a year under a recommendation from a Bush-appointed commission in 2001. A key financial-industry concern is that, at least initially, the accounts may be too small to be profitable for most companies to manage, given the paperwork and investor hand-holding that could be required.

"None of my members is salivating at the prospect of managing millions of small accounts," said Marc Lackritz, president of the New York-based Securities Industry Association, the brokerage business' chief trade group.

In time, private accounts would become a pie too enormous to ignore, many analysts say. Some estimate that annual inflows to the accounts could reach $75 billion in the first few years alone.

Given the sums involved, "Social Security reform could have a great impact on the financial-services industry," Ken Worthington, an analyst at brokerage CIBC World Markets in New York, wrote in a November report.

The Bush commission's recommendations addressed the issue of small account size by proposing that private contributions initially be placed in one of a handful of pooled stock or bond accounts overseen by the government.

Conceivably, the government would contract with private money managers to invest the assets, most likely in so-called index funds that would replicate the performance of broad market gauges such as the Standard & Poor's 500 stock index.

Under that scenario, the first Wall Street beneficiaries of a shift to private accounts could be companies such as Barclays Global Investors in San Francisco and Valley Forge, Pa.-based Vanguard Group, which run large index funds for minimal fees, Worthington said.

As the accounts grow in size, other brokerage and mutual-fund firms likely would be permitted to take over management of the money at investors' discretion, he said.

As workers retired, the insurance industry could gain a role, offering to turn the accounts into annuity contracts that would pay workers a set monthly sum until they die.

Concern about fees

At every level, financial companies would expect to be paid for their services.

The issue of Wall Street fees has become a hot button for groups on both sides of the debate.

Financial companies betray "an enormous conflict of interest" if they support private accounts, said Bill Patterson, director of investments at the AFL-CIO. "This is driven by fees."

A study last year by Austan Goolsbee, University of Chicago economics professor, asserted that the accounts could generate fees for the financial industry worth $940 billion, in current dollars, in 75 years.

The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that supports Social Security privatization, assailed Goolsbee's study as "riddled with errors, unjustified assumptions and sensational but meaningless numbers."

The Securities Industry Association last month said that Wall Street firms could take in as little as $39 billion in fees from Social Security private accounts, in current dollars, in 75 years. That would amount to 1.2 percent of the estimated total revenue of the financial sector in that time period, the group said.

Some financial-company executives privately express concern that fees could become a trap for them.

They worry about how tightly the government would regulate every aspect of a privatization program, and whether future Congresses could impose fee caps or other restrictions that suddenly would turn a profitable business into a loser.

"Once everybody has these accounts, the incentive for Congress to regulate them would be very strong," said Derrick A. Max, executive director of Alliance for Worker Retirement Security, a Washington-based coalition set up by the National Association of Manufacturers to lobby for private accounts.

A cultural shift

Even so, Wall Street sees benefits from Social Security privatization that could go well beyond the fees generated by the accounts themselves.

Bush has championed private accounts as part of his "ownership society" agenda, under which Americans would take more control of their financial futures and rely less on Uncle Sam.

For many in the financial industry, that philosophical shift has great appeal, because it could lead to more private saving and investment over time, said Paul Schott Stevens, president of the Washington-based Investment Company Institute, the mutual-fund industry's chief trade group.

Fueled in part by the rise of 401(k) company savings plans, the percentage of U.S. households that own stock or bond mutual funds has risen, from 25 percent in 1990 to about 48 percent.

"We are much more now a nation of investors," Stevens said. "We think this is a valuable and beneficial thing."

Younger workers, in particular, may well find the idea of private Social Security accounts attractive for their long-term earnings potential, he said.

Stevens said the institute so far has not endorsed privatization, and added, "we are not lobbying" for the accounts.

Behind the scenes, however, several financial giants are lending support to the privatization effort.

Max said the Schwab brokerage has helped to fund his group's efforts to push private investment accounts.

The libertarian Cato Institute in Washington, which also is lobbying for privatization, has received funding from insurance titan American International Group Inc., mutual-fund company T. Rowe Price Group Inc., brokerage E-Trade Financial Corp. and others for studies about the subject, said Michael Tanner, Cato's director of health and welfare studies.

Both Max and Tanner said the amounts contributed by financial companies have been modest so far.

"It's a small check," Max said of Schwab's contribution.

"People say I'm in the pay of Wall Street," Tanner said. "I wish I was. They give very little to support this."

|

|