|

|

Q&A: The US Social Security System

By Mark Tran, The Guardian

February 3, 2005

What is social security?

The centrepiece of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, the social security programme provides a stable monthly income for the elderly. Some 47 million Americans receive social security cheques of an average close to $1,200 (£638) a month. Around two-thirds of pensioners rely on social security for the majority of their income. For a fifth of them, social security is their sole source of support.

How is it funded?

Money for social security is raised through a tax on pay. The tax is 6.2% of an employee's income paid directly by the employer, and 6.2% deducted from the employee's pay, yielding an effective rate of 12.4% of an employee's income. These payroll taxes are paid into the social security trust fund maintained by the US treasury. A retired person receives social security benefits based on the total accumulation of social security payments over their working life.

Why does Bush want to change the system?

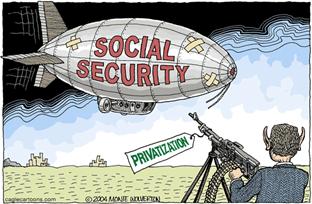

The president says that on its present path, social security is heading for bankruptcy. The centrepiece of the Bush plan is the personal investment account, diverting around one-third of individuals' payroll tax that would be invested in the stock market with its attendant risks and rewards.

Is the system going bust?

There is a big debate over whether social security is in crisis. As things stand, the revenues from the payroll tax exceed the amount paid out in benefits. At the end of 2003, the cumulative excess of social security taxes received over benefits paid out stood at more than $1.5 trillion.

So where is the problem?

As baby boomers reach retirement age, the system is projected to go into deficit in 2018, and cash will start to be withdrawn from the trust fund. The congressional budget office predicts that the trust fund will run dry in 2052. The administration forecast is 2042.

So why is there talk of bankruptcy?

For those, like Bush, who want root-and-branch reform, bankruptcy is the favoured term in order to create a sense of crisis that needs urgent solution. For those who think the system just needs tweaking to remain healthy, it's a "financing problem". The facts point toward the latter.

What is the scale of the problem?

Even after the trust fund is gone, social security revenues will cover 81% of the promised benefits. The congressional budget office points out that extending the life of the trust fund into the 22nd century with no change in benefits would require additional revenues equal to only 0.54% of GDP. That is less than 3% of federal spending and less than US spending in Iraq. The amount is also a quarter of the revenue lost each year because of Bush's tax cuts, roughly equal to the fraction of those cuts that goes to people with incomes over $500,000 a year.

How can the shortfall be covered?

Democrats - who strongly oppose the Bush plan - have argued for raising the ceiling on the payroll taxes above the current $90,000 cap and lifting the retirement age. Laura D'Andrea Tyson, a dean of the London Business School has another solution. Over the next 75 years, the Bush tax cuts, largely aimed at wealthy Americans, are projected to cost between $10 trillion to $12 trillion. Simply paring the cuts back by a third and putting the cash into social security would cover any shortfall.

What about Bush's private accounts idea?

Critics say the assumptions behind the plan are unrealistic. According to Paul Krugman, a leading US economist, proponents of privatisation assume that investing in shares will yield a high annual rate of return, 6.5 or 7% after inflation, for at least the next 75 years. "Without that assumption, these schemes can't deliver on their promises. Yet a rate of return that high is mathematically impossible unless the economy grows much faster than anyone is now expecting," Mr Krugman wrote in the New York Times.

What about the impact on the budget deficit?

By allowing younger workers to shift cash away from the trust fund, the Bush administration would deprive the trust fund of a large chunk of revenue. The government would be forced to borrow a further $2 trillion in the next 10 years to plug the gap, on top of the already record $5 trillion deficits run up in the Bush administration's first term. Wall Street's role in managing the funds is also controversial. Investment bank fees would effectively be deducted from social security taxes, eating into the amount that would be invested.

|

|