back

|

|

A

Sketch of an Older Ukrainian

By Dmytro Komshyn, Global Action on Aging

October

10, 2003

Ukraine

is located in southeastern

Europe

, and its largest neighbors include

Russia

,

Poland

,

Romania

and

Byelorussia

(

Belarus

). The country has

about 49 million people in an area about the size of

Texas

, making it the

biggest European country next to

Russia

and

Turkey

. The population

has been shrinking in the last few years, decreasing by almost 3 million

people from 1991 to 2003, and the average age is getting older. Today

people over 60 comprise more than 20% of the total population and in the

next decade this number is projected to increase by 9%.

With

the exception of a short period before 1920,

Ukraine

had been

dominated by its larger neighbor,

Russia

, for centuries

before the former

Soviet Union

broke up in 1991, making

Ukraine

an independent

state. Although the fall of communism led to freedom of speech and

religion, it was disastrous for the Ukrainian economy. Many towns have an

unemployment rate in excess of 50 percent. The standard of living for most citizens has declined by more than

50 percent since the early 1990s. The larger cities have some evidence of economic growth,

but severe poverty plagues not only the cities but especially the

countryside and villages. However, while

Ukraine

was among the

poorest European nations in the mid-1990s, the country has enjoyed a

steady 5-6% growth rate in the last four years. The lives of Ukrainians

are improving and many people are happier now than 13 years ago, but a

large part of the population still lives below the poverty line. Most of

these people are elderly.

The collapse of the

Soviet Union

disproportionately affected the senior citizens of my country. Older

persons’ life long savings disappeared due to inflation rate up to

10000% a year at its peak in 1993, most of seniors lost their jobs due to

severe competition with younger people, and those who were on a state

pension received virtually nothing. The

USSR

pension system was accumulative and relied heavily on the state, but

Soviet pensions were relatively sufficient for a comfortable standard of

life. Today the average pension is slightly above 35% of the average

salary; in

USSR

those numbers were almost the same. However, the Soviet government

provided pensions above the minimal Monthly Maintenance Rates (MMR), and

in the 1990s the pensions were two times and a half below the Monthly

Maintenance Rate. After the break up of

USSR

, the survival of retired people was left in their own hands. The

Ukrainian government tried to improve the situation, but due to lack of

budget funds it could do nothing. The economic growth of the last years

made it possible to increase the pensions in

Ukraine

, but the old pension system, based on the Soviet scheme, could not

provide enough flexibility in the constantly changing demographic and

economic environment. According to the latest data, the average pension in

Ukraine

is about 30-35 USD a month, up from 6 USD in 1995. The country still

provides free rides for the elderly on all public transportation including

railways, but the number of privileges for the elderly is declining.

Ukraine

is transforming into a market economy where additional social costs are

difficult to budget properly. One might ask, how have older people managed

to survive through the worst years of transition in Ukrainian history with

their 6 USD pensions? That is

not an easy question to answer, taking into account the fact that 95

percent of senior citizens became poor after enjoying a middle class life

in the Soviet era.

Let

me tell you a story of someone who still lives in

Ukraine

and who went

through the process of becoming a poor senior citizen. Her story is

typical for millions of elderly Ukrainian women and men.

Galina,

in her mid 60s, lives in the suburb of the Ukrainian capital,

Kiev

. She has been

working as a teacher in one of the state secondary schools. Galina was

devoted to her work, having served in the same school for 35 years. The

fact that she had non-stop employment at one place has entitled her to a

higher-than-average pension compensation when she retires. Galina was sure

that her pension would allow her to have a quiet life in her own apartment

after leaving her job. She also had her personal savings in the Soviet

Savings bank, and she was going to help her children financially to adjust

to adult life.

At

the beginning of the 1990s, her plans changed radically. The inflation in

the country ruined the expectations of millions of people, as their bank

savings turned into nothing. Galina was planning to buy a new apartment

with her substantial savings, but suddenly all of that money was worth

only a table and chairs. When she turned 55, she could officially retire

(the retirement age is 55 for women and 60 for men). Galina

lives in the area contaminated by radiation due to the Chernobyl disaster,

as millions of other Ukrainians, and the state allows early retirement for

the victims of the disaster (50 for women and 55 for men). However,

Galina continued her work so that she could be useful to her two children,

one of whom was a university student and another a beginning lecturer at

the technical university, receiving a salary less than her monthly wage.

At that same time, Galina lost her husband. It is worth mentioning that

Ukrainian men were affected more than women by the collapse of the

Soviet Union

. Men live 61 years on average, down from 66 years 13 years ago, for

women, life expectancy dropped to 73 from 76 at the beginning of the 1990s.

As

much as Galina wanted to continue to work at her school, she felt that she

had to leave. Young teachers needed jobs, and they had no other sources of

income, as she did with her then-miserable pension and school salary.

Practically free housing, utilities and subsidized food became the

memories of the past. Her pension comprised 70% of the monthly utilities

bill, and she had no way out. While young people were enjoying freedom and

new possibilities, Galina could not compete with them and their knowledge

of foreign languages and computers. She had no phone in her apartment and

was watching a black and white TV-set. Stranded with their own problems,

her children tried to help her but it wasn’t enough. At that time,

millions of elderly were in despair and were bitterly nostalgic for the

old Soviet times. Life was

getting worse and worse.

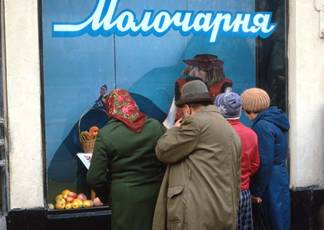

Galina

and older people like her did not have enough money to buy food, so the

only way to survive was to get food by some other means. The state gave

anyone who was willing a chance to grow gardens for vegetables, fruits and

potatoes. Former, teachers, doctors, engineers suddenly became farmers.

The areas around big cities turned into endless small fields. Dachas

(summer houses) that were mainly used for recreation activities in

Soviet Union

now turned into

small farms. People in the rural areas left state collective farms and

started to learn again how to run private business, grow cattle and

poultry, and sell their own products. The country that had previously a

rural population only around 26% became a garden again. The “breadbasket

of the former

Soviet Union

” could not feed

its own people, but now people did not rely on the government for food.

Instead of going to seaside or mountain resorts as Galina used to, she

went to the forest to pick berries and mushrooms with her

neighbors and friends. She learned how to sell food extras on the local

market and how to exchange her harvest with her neighbors. But she saw her

former colleagues from the Education or Health departments begging on the

streets or collecting empty cans from the garbage bins. I still remember a

neatly dressed old lady crying in the supermarket. She was standing in

front of the glittering glass and kept saying, “I do not remember how

butter tastes.” Even tiny pensions were delayed for 3 or 4 months. The

electricity supply was regulated and there were endless nights without

electricity even in winter. The hospitals were asking patients to bring

their own medications and food. The elderly became outcasts in society.

That was

Ukraine

in the 1990s: the

center of

Europe

, the most

industrially and agriculturally developed former Soviet

Republic

. Galina

and older people like her did not have enough money to buy food, so the

only way to survive was to get food by some other means. The state gave

anyone who was willing a chance to grow gardens for vegetables, fruits and

potatoes. Former, teachers, doctors, engineers suddenly became farmers.

The areas around big cities turned into endless small fields. Dachas

(summer houses) that were mainly used for recreation activities in

Soviet Union

now turned into

small farms. People in the rural areas left state collective farms and

started to learn again how to run private business, grow cattle and

poultry, and sell their own products. The country that had previously a

rural population only around 26% became a garden again. The “breadbasket

of the former

Soviet Union

” could not feed

its own people, but now people did not rely on the government for food.

Instead of going to seaside or mountain resorts as Galina used to, she

went to the forest to pick berries and mushrooms with her

neighbors and friends. She learned how to sell food extras on the local

market and how to exchange her harvest with her neighbors. But she saw her

former colleagues from the Education or Health departments begging on the

streets or collecting empty cans from the garbage bins. I still remember a

neatly dressed old lady crying in the supermarket. She was standing in

front of the glittering glass and kept saying, “I do not remember how

butter tastes.” Even tiny pensions were delayed for 3 or 4 months. The

electricity supply was regulated and there were endless nights without

electricity even in winter. The hospitals were asking patients to bring

their own medications and food. The elderly became outcasts in society.

That was

Ukraine

in the 1990s: the

center of

Europe

, the most

industrially and agriculturally developed former Soviet

Republic

.

People,

and especially the elderly, had no choice but to work, either in their

small gardens or selling things on the market. Spring, summer and autumn

were dedicated to working in the suburban fields. If one happened to

travel around

Ukraine

at that time, one

could see numerous people working in those tiny gardens along the highways

and railroads. The old “family help cycle” has changed, but its core

remained untouched: elderly fathers and mothers kept providing food to

their children. In turn, children became able to assist their parents

financially. The country was slowly gaining its strength again. Galina

decided to take a low paid part-time job at a school for children with

health problems. At the end of the 1990s when production started to rise,

fewer and fewer people wanted a job within the social or state system. The

situation was changing: the same schools that did not want Galina to work

when she retired now did not enough teachers and asked her to come back.

However, Galina seemed to enjoy her new lifestyle. She had her little work

at school and she had her garden.

Recently,

many old people have left their gardens and working children are

earning enough to assist their parents.

Ukraine

introduced

compensation packages for the retired and low income families to pay for

house utilities. Due to a huge transformation in the agricultural sector,

food became more affordable. Galina kept her garden, but grows fewer

tomatoes and potatoes and more flowers and strawberries. She can afford

most basic food, but her garden allows her to save money. Growing her own

food is not a matter of survival any longer.

Galina

survived the worst period of her life, but there are other elderly who

have nobody to rely on except for themselves and the state. Their bad

times are still not over.

Ukraine

is struggling to

increase pension payments, and every year people see those small

additional payments.

Ukraine

will begin a

pension reform program in 2003 and 2004. Instead

of a unified state pension fund, there are plans to introduce three levels

of pension provision: solidarity or state system, accumulating or savings

insurance system and non-governmental pensionary provision or personal

savings.

Galina

hopes that her 35 years of work will be rewarded by the state one day. At

present, her pension does not differ much from the other age pensions, i.e

a pension for those who did not work nor had a shorter working experience.

She still hopes that one day she will discover that she is not poor

anymore. Yet, some of her friends will never see that time.

The

Ukrainian government has adjusted the lost savings of its citizens in the

former Soviet Savings bank. Two years ago the first adjusted amounts were

paid to persons over 90. The government increased the pensions to 50% of

the monthly MMR this August. The government started to increase pensions

by 4% to 10% for every extra year worked over the retirement age. The

pensions are calculated not by the salary of the last 5 years worked (in

our case those were inflated amounts) but by any 60 calendar months of

payments throughout the whole work experience. Some pensions for

government workers, former military and victims of

Chernobyl

have been

increased, and they are higher than the average wage now.

Galina

may be considered to be lucky. She was a highly educated professional. Her

children were always there to help her, and she kept her links with the

local community. Many retired Ukrainians had neither family nor adequate

work experience. Some lived in huge apartment blocks, away from the

gardens and community support. Some were abandoned by everyone in the

remote forest villages. Some struggled with health problems.

But,

at least people like Galina have hope for better times. She worked hard

her whole life and she, as well as millions other Ukrainians, deserve to

see their dreams come true.

Copyright

© 2002 Global Action on Aging

Terms of Use | Privacy

Policy | Contact Us

|