|

The Longevity Revolution

By Bob Moos, Dallas News

March 23, 2008

World

TROY OXFORD/DMN Staff Artist

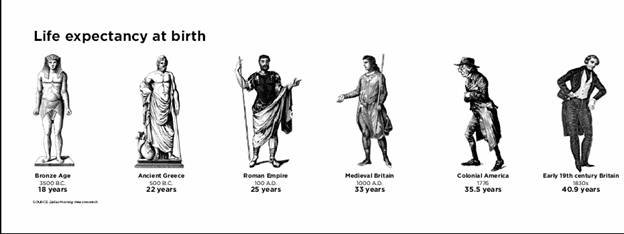

Infant and childhood mortality can take its toll on life expectancy. That was especially true in earlier centuries, before public-health measures and medical breakthroughs improved someone's chances of reaching adulthood. In imperial Rome, for example, life expectancy at birth was 25. But those Romans who survived childhood had an average life expectancy of 40.

Mankind's greatest triumph of the last century was not the mastery of flight, the invention of the computer or the recognition of rights for women and minorities. As huge as those achievements were, they were overshadowed by something more profound.

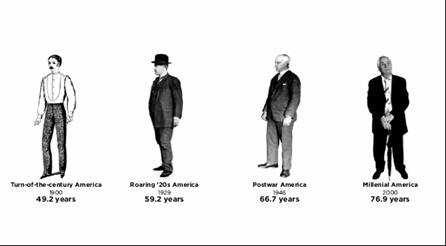

Over the past 100 years, humankind fulfilled the age-old dream to extend life, by making bigger gains in life expectancy than during the previous 50 centuries. In 1900, Americans lived an average of 49.2 years. By 2000, they lived to 76.9 years. Better public health, medical breakthroughs and health care reforms added almost 30 years to life and made old age more than a curiosity. And the best may be yet to come. Scientists expect biomedical research to lengthen life even more in the 21st century.

Dr. Robert N. Butler, who has spent his career studying older people and caring for them, calls the extraordinary human accomplishment "the Longevity Revolution" and says that "what was once the privilege of the few has become the destiny of the many."

Dr. Butler's 50-year career has been one of firsts. A pioneer in the field of aging, the gerontologist became the founding director of the National Institute on Aging in the '70s, created the first geriatrics department at a U.S. medical school in the '80s and established in the '90s the International Longevity Center, the first policy research organization devoted entirely to aging.

More than 30 years ago, his Pulitzer-Prize-winning book – Why Survive? Being Old in America –first raised the topic of growing old in a country preoccupied with youth. He has since written or edited a dozen other books. But his just-published work, The Longevity Revolution, has been the one most anticipated by professionals in aging.

Dr. Butler hopes to engage the nation in another discussion about old age, this time about the challenges posed by the unprecedented gain in life expectancy. That kind of public conversation can't happen too soon. Though the Longevity Revolution has been a century in the making, we as Americans haven't prepared well for it.

We haven't figured out how to accommodate older people's desire to work or volunteer so that the additional years become productive for them and rewarding for society. Retirement can't mean idleness if it's to last a third of someone's adult life.

Nor have we trained enough primary-care physicians to differentiate and treat the interacting medical conditions that beset the elderly. Of 144 medical schools in this country, only about a dozen have geriatrics departments.

And we still haven't created a comprehensive system of long-term care that doesn't impoverish or dehumanize people. Too many of the old and frail spend their final days in nursing homes, waiting for the next meal to break the tedium.

We have been in denial about growing old. Our neglect shows, and it's not pretty.

"It's discomforting for people to think about their later years," Dr. Butler explained during a recent interview about his book. "Most individuals don't plan for old age. I suppose they figure it will get here soon enough."

We could all take a cue from this physician and gerontologist, who turned 81 last month. He walks the talk about healthy aging. On weekdays, he's on the job at his policy research center.

On weekends, he's out and about with his fellow walking-club members, covering five to six miles in Manhattan before lunch.

Dr. Butler keeps going and going because he's convinced that, sooner or later, he'll break through the public's indifference or denial about aging – much like Al Gore's single-mindedness about the dangers of global warming finally pricked the public's consciousness.

Maybe, at long last, we've reached a teachable moment on aging, too. This year, the baby boomers – the generation that always thought it could defy old age – began qualifying for early retirement benefits from Social Security.

Dr. Butler believes that one doesn't have to be a doomsayer wailing about "apocalyptic demography" to worry about those 78 million boomers. Even "people of good will," he says, have questioned whether the country can afford that generation's golden years. Many of the oldest members who just turned 62 will live into their 80s and 90s.

There are many reasons to think boomers are a generation at risk.

Many can't depend on the traditional pensions their parents' generation could tap. They will have to take more responsibility for their financial security late in life. Yet half of them have retirement savings of less than $50,000.

Spiraling medical costs will only exacerbate the problem. A typical couple needs $200,000 to cover health care costs during retirement, a figure that the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College estimates will more than double by 2040.

Our health care system is also ill equipped to look after an aging population. It was designed to treat diseases more than promote health. Its primary concern has been acute illnesses, not the chronic conditions that manifest themselves in old age.

Dr. Butler doesn't underestimate the challenge of reorienting the country to its older population, but he remains optimistic the boomers will "transform what it means to live a long life," just as they have already redefined the earlier stages of life.

He disputes the gloom-and-doom thinking that longevity poses an economic burden for the nation. The gerontologist views this new time of life as an economic opportunity.

The idea that older people are necessarily a drag on society has no place in Dr. Butler's universe. The man credits his survival and good fortune to his grandparents, who raised him during the Depression and helped him realize his boyhood dream of becoming a doctor.

The notion that a society's wealth creates good health tells only half of the story, he argues. It works the other way, too – a long life engenders wealth.

"People who stay healthy are good workers, continue to save and invest, and remain productive in their later years," he said. Longevity also gives rise to the "silver industries" – the many businesses that cater to the senior market.

A whole cadre of business consultants has sprung up to advise companies on how to cash in on an aging population. Increased life expectancy will be a boon for senior-living companies, financial services, anti-aging products, pharmaceuticals, travel, medical equipment and home health care services, among other businesses.

Still, Dr. Butler is up against more than public indifference in making people understand that the Longevity Revolution is a good thing and that they're really advocating for themselves in the long run when they're advocating for older people.

The gerontologist was the first to coin the term "ageism" 40 years ago in describing public resistance to senior housing, and the systematic stereotyping and discrimination against older people may be as embedded in our culture today as it was then.

Ageism reveals itself in the subtlest ways.

Our language is filled with abusive terms such as "codger," "geezer" and "old goat" that wouldn't be acceptable to any other group.

Ageism has even crept into this year's presidential campaign.

David Letterman recently joked that John McCain "kind of looked like the old guy at the barber shop or like a Wal-Mart greeter." At 71, Mr. McCain would become the oldest person elected to a first term as president.

Yes, it was just late-night TV humor, but how would the audience have reacted to the comedian "having fun" with Barack Obama's racial background?

"We've made great progress in this country in eliminating racism and sexism, but I'm afraid I can't say the same for ageism," Dr. Butler said.

Though seemingly innocuous, the repeated stereotyping of older people can sometimes incite or perpetuate blatant discrimination or gross abuse.

Advocacy groups that are trying to create more opportunities for older workers continue to run into employers who view them as rigid, unwilling to learn new skills or likely to quit their jobs after a short while.

At the Senior Source in Dallas, executive director Molly Bogen and her staff serve 32,000 older adults every year, many of whom call on the nonprofit agency after hearing from others that they're too old to work anymore and don't matter.

"Ageism is more than a concept with us," she said. "We see it every day in the drawn faces of our clients."

One of the Senior Source's more popular services is its job counseling program, which helps unemployed older workers polish their résumés and interview skills. It gives them the confidence to overcome prospective employers' bias.

"The number of older Americans will double over the next 25 years, yet our culture is so youth-oriented," Ms. Bogen said. "I'd say we're all on a collision course."

In its ugliest form, ageism can turn abusive. Five million older Americans, many suffering from dementia, fall victim to financial exploitation every year. Almost always, it's at the hands of the people entrusted to care for them.

As long as ageism festers, older people will be seen as "them," unworthy of compassion or even attention.

The bigotry against older adults also plays into the hands of politicians and pundits trying to fan a generational conflict by arguing that "greedy geezers" will drain the tax coffers and deny younger generations their due.

Dr. Butler pins his hopes on the boomers because they will have the numbers and political savvy to rewrite the rules of aging. They've been the driving force behind social movements before in their lives, so why not again?

High on the boomers' political agenda will be creating opportunities for those who want, or need, to continue working past the traditional retirement age.

The marketplace itself will solve part of the problem, as a projected labor shortage in certain industries will make employers more willing to hold onto their older employees. But Dr. Butler suggests nudging other employers, by offering financial incentives or eliminating current barriers to hiring older adults.

He proposes, for example, allowing people to qualify for Medicare at 55, instead of 65, and making it the primary payer of their health care. Older workers would then become less expensive and more attractive to businesses.

Keeping people in the workforce longer so that they can pay into Social Security, rather than draw benefits from it, would offset some of the reform's costs, he argues.

If this country is to adapt to a longer life expectancy, the reforms to Medicare, Social Security and other programs will need to be fair to all generations. Any changes that even appear to favor boomer retirees at the expense of younger, working generations will only lead to complaints that "greedy geezers" are indeed alive and well.

One group already moving to head off generational conflict is the one most closely identified with older generations. Though AARP still limits membership to people 50 and older, it's developed a message to resonate across all ages. Its recent ads feature people of different generations and tout AARP as "an organization for people who have birthdays."

AARP has carried the multigenerational theme into this election year, as its Divided We Fail campaign follows political candidates across the country to call attention to issues like affordable health care and financial security for all Americans.

Those initiatives may help dispel the perception that boomers are a self-indulgent generation. But the most convincing evidence will come when the boomers take these additional years of life and use the time to do something beyond themselves.

Six in 10 boomers in their 50s have told pollsters that they would like to switch careers someday and find jobs with a higher, social purpose. Many have set their sights on education, health care, the ministry and social services.

Boomers looking for meaningful work could provide the answer to the widening labor shortages in teaching and nursing as well as form an engine for social change. For a generation that came of age in the '60s, that kind of activism should have great appeal.

Dr. Butler may have good reason for his optimism that the Longevity Revolution will pay a dividend rather than exact a price.

"We can meet the challenges of an aging population," he predicts. "Our new longevity is something to celebrate and build on."

Bob Moos, a baby boomer, is a Dallas Morning News staff writer who covers aging issues. His e-mail address is bmoos@dallas news.com.

More Information on World Health Issues

Copyright © Global Action on Aging

Terms of Use |

Privacy Policy | Contact

Us

|