|

Making Room for Aging Relatives

By Pedro Arrais, Times Colonist

February 6, 2010

Canada

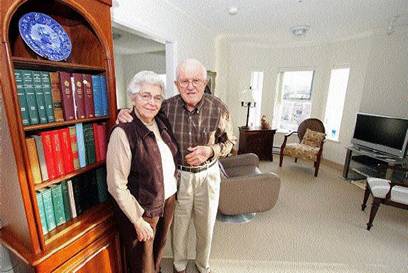

Abby and Ken Thompson chose not to move in with their middle-aged children, and took a suite in an assisted living complex. Such "retirement resorts" illustrate the kind of home design that suits seniors, who might have health or mobility issues.

Photograph by: Photos by Bruce Stotesbury, Times Colonist

The children may have just moved out but the generation of boomers can't rest yet, as they prepare to renovate their houses to accommodate the needs of aging parents.

In a survey done in 2002, Statistics Canada reported three in 10 adults aged 45 to 64 (or 2.6 million people) had unmarried children under 25 at home. Of this number, 712,000 were also caring for a senior. Of these people, 21 per cent (about 150,000) were looking after two seniors.

Balancing the care of seniors and children is not a new phenomenon. The main difference between the past and the present is that most working-age women are now in the workforce; few women are full-time homemakers. While child-care services have evolved to look after the needs of the young in recent decades, there have been fewer resources devoted to the growing number of seniors.

But some seniors, while appreciative of the efforts their children to look after them, are independent enough to find suitable accommodation on their own.

"I believe living with one's children can put a strain on the relationship," says Abby Thompson, who lives independently in a retirement home with her husband Ken. "Some of our children have homes with suites, but we turned them down so that we can live on our own."

The Thompsons -- she is 85 and he 84 -- lived in a house in Sooke for 23 years. Last year, they moved into a two-bedroom suite in the Ross Place Retirement Residence in Victoria.

Their experience is typical, say experts on aging.

"Most seniors, given the chance, want to stay independent as long as they can," says Dr. Elaine Gallagher, professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Victoria. "While they are appreciative of their children buying homes with suites for their needs down the road, many have come to treasure their independence."

While children are well-meaning, most in-law suites need to overcome three common architectural elements that serve as barriers for universal accessibility for people who might need to use wheelchairs or walkers:

1. Doorways that aren't wide enough for wheelchairs to get through.

2. An entry door sill that is not level.

3. Bathrooms on the main level of the suite that are too small for a person confined to a wheelchair to use.

Other items, while not restricting, are senior-unfriendly. They include:

1. Suites with thick-pile wall-to-wall carpeting that significantly increases the amount of effort necessary to propel an individual confined to a wheelchair across the room.

2. Rooms and hallways designed without thought for adequate turning spaces.

3. Bathtubs not equipped with lower sides and baths or showers lacking grab bars, which can save seniors from a nasty fall.

The physical renovations to make a house senior-friendly are not onerous and, depending on the layout, relatively straightforward.

The real challenge, says Gallagher, who has over 40 years experience in the field, is to have a human back-up system or community support in place to provide necessary home care and respond to emergencies. (We'll explore some of the services available in a future article.)

According to the Statistics Canada report mentioned above, for those Canadians caring for their parents, only 25 per cent had friends, relatives and neighbours to help, resulting in 70 per cent of them reporting stress in their lives, compared with 61 per cent of workers with no child or elder-care responsibilities.

The report found while eight in 10 caregivers worked, caring for an elderly person could lead to a change in work hours, refusal of a job offer or reduction in income.

"Sometimes it's physically and mentally beyond what one person can supply," says Gallagher.

Victoria has a number of retirement residences that can fill the gap.

Bill Rankin, general manager of Ross Place Retirement Residence, says: "Most of our clients come to us after they have experienced a tipping point in their lives.

"Usually it's after an incident, such as a fall, an illness or they find they now need help with some part of their everyday activities, such as dressing."

His clients, most of whom are in their 80s or older, are provided with a choice of independent or assisted living, depending on their needs. (We'll explore some of the options available on south Vancouver Island in a future article in this series.)

"Instead of sitting at home watching TV alone, we offer seniors a community-based environment to interact with their peers," says Rankin. "It's a new stage of their lives and they get to participate in activities and meet other people."

A person's twilight years are supposed to comfortable and free from stress. Demographics point that the market will likely burgeon as boomers become seniors themselves in the years ahead. Seniors and their families need to assess their changing needs and adequately plan to find the accommodation that best suits their lifestyle and personality.

"I have no regrets about selling my house and moving here," says Abby Thompson, whose children helped her find, evaluate and choose her new home. "I accept this change as just another adventure."

More

Information on World Health Issues

Copyright © Global Action on Aging

Terms of Use |

Privacy Policy | Contact

Us

|