Atrial

fibrillation: strategies to control, combat, and cure

By: Robert W. Griffith, MD

Health and Age, July 26, 2002

.

Introduction

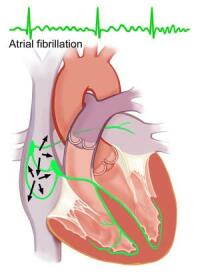

Normally the heart beats regularly; when one's

resting, it's a little slower or faster, according to the respiration --

this is called 'sinus rhythm'. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the commonest

heart 'arrhythmia', or irregular heartbeat. It's a very irregular and fast

heart rhythm involving the upper chambers (atria) of the heart.

AF is more common as people get older, but it's also

being seen increasingly often, irrespective of age. It can occur in

otherwise healthy people without any obvious cause. More often, however,

it is seen in people with high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, an

overactive thyroid, or who drink too much alcohol.

Today, more than 5% of those over 65 have AF. It's

commoner in men, and men who have had a heart attack (myocardial

infarction, or MI) are at especial risk. Rarely, AF runs in families.

The big threat of AF is an increased likelihood of

stroke; a stroke may occur in 1% to 2% of patients in their 50s, and in

20% of those in their 80s. Mortality rates in people with AF are double

the norm, due to stroke, heart failure, or MI.

What happens in atrial fibrillation?

Normally, the natural pacemaker of the heart situated

in the atria sends an electrical signal to the rest of the heart, causing

the whole heart -- both atria and ventricles - to contract. During AF, the

atria beat very rapidly and out of rhythm with the rest of the heart; this

interferes with the overall pumping action of the heart.

The irregular fast rhythm of AF arises from one or

more abnormal pacemakers, or 'excitable foci', that are often situated

just inside the pulmonary veins as they enter the atria; occasionally the

foci may be in the nearby part of the superior vena cava (the great vein

draining the upper body). How a focus is triggered, and what triggers it,

is still unclear.

In AF, the period of time after an electrical signal

during which the tissues cannot be stimulated again (the 'refractory

period') is shorter than normal. This allows more frequent, irregular

waves of contraction in the atria. The atria adapt to this by

progressively shortening their refractory periods, leading to the adage

"atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation" -- i.e. left

alone, the condition tends to worsen.

With the atria failing to contract properly, blood

can pool, or move very slowly ('stasis'). This is most marked in the left

atrium, where a clot (or 'thrombus') can form, bits of which can, at any

time, enter the blood stream and block a small brain artery -- thus

causing a stoke.

The types of AF

A first episode of AF is called 'acute atrial

fibrillation'. Subsequent episodes are called 'recurrent'. If the episodes

stop on their own, they're termed 'paroxysmal'.

If the episodes are so frequent or long-lasting that

the physician needs to stop them (this is called cardioversion), it's

'persistent AF'. And if they cannot be stopped by cardioversion, or if

they have lasted a year without such an attempt, AF is regarded as

'permanent'.

When it's known that the fibrillation originates at

one or more foci in an otherwise normal heart, it's called 'focal AF'.

This type (which may be paroxysmal or permanent) is commoner in patients

in their 50s and 60s, and is three times

more frequent in men.

Symptoms and diagnosis of AF

Some people will have no symptoms; others will have

some shortness of breath, and a feeling of palpitations or fluttering in

their chest. Fainting can occur, and there can be chest pain.

AF is diagnosed from the history, a clinical exam,

and an electrocardiogram (ECG). Wearing a heart monitor (a Holter monitor)

for a period can help detect paroxysmal AF if there are no symptoms to go

on. Doctors will often order an echocardiogram, to look for changes in the

size and functioning of the 4 heart chambers.

Treatment

First, the heart rate must be slowed to a more normal

rate. This will usually decrease symptoms. Calcium-channel blocking drugs

(e.g. diltiazem, verapamil) or beta-blockers (e.g. sotolol) are used for

this.

To prevent the formation of thrombi in the left

atrium, a blood thinner, or anticoagulant, should be given; warfarin is

the usual choice. This is important if AF has existed for more than 48

hours and an attempt to restore normal (sinus) rhythm is planned. In case

of doubt, a special exam (trans-esophageal echocardiography) can detect

the presence of atrial thrombi.

Re-establishing sinus rhythm (called 'cardioversion')

can be done using medication, or by an electrical shock. There are various

types of drugs called antiarrhythmics that are intended to stop heartbeat

irregularities. Those used for medical cardioversion include flecainide

and amiodarone. As they may have serious side effects, medical

cardioversion must be done in hospital.

Electrical cardioversion can be 'external' or

'internal'. External cardioversion involves using electric paddles applied

to the chest wall, under general anesthesia. The shock halts the abnormal

fast pacemaker and allows the normal pacemaker of the heart to take over.

Success rates range from 65% to 90%. If this doesn't restore normal

rhythm, the patient can be given an antiarrhythmic drug for a short

period, and the procedure repeated.

Internal electrical cardioversion involves having

small tubes that carry electric wires passed under the skin to deliver

shocks at specific sites in the heart (usually in the right atrium); this

is done under general anesthesia. Using this technique, normal rhythm is

restored in 90% of those cases where external cardioversion has failed.

Once normal rhythm has been achieved, it must be

maintained. Sotalol, flecainide, propafenone, and amiodarone are all

effective medications for suppressing paroxysms of AF. In some cases,

surgery is done to implant an atrial pacemaker. (This is different from

the usual pacemaker, which regulates the ventricular beats.) Atrial pacing

is effective; it suppresses the undesired focal beats and improves

electrical conduction.

It's also possible, using an approach similar to

internal cardioversion, to detect the site of abnormal foci and then

destroy them by radio-frequency energy delivered along the wires. In

patients with only one abnormal focus, success rates are near 90%, but

this falls to about 50% in those with three or more foci.

Finally, a surgical procedure, the Maze operation,

involves cutting the atria into segments and then rejoining them. It

reduces the amount of atrial tissue available for fibrillation to 'breed'.

Success rates are high, but the procedure is quite risky.

Preventing stroke

Should people with AF be on long-term anticoagulants?

It's a matter of balancing the risk of side effects (chiefly hemorrhage)

against the risk of having a stroke. Someone with AF is at greatly

increased risk of stroke if they are over 65, have had a previous stoke or

transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), have diabetes, high blood pressure, or

heart failure. It's been shown that anticoagulation using warfarin reduces

the risk of thrombotic stroke in AF patients by 68%, and cuts mortality by

33%. Aspirin is much less effective than warfarin.

Conclusions

The management of AF has improved in recent years, so

that more attention is being paid these days to ways of curing it, rather

than suppressing paroxysms or future episodes. For those patients who

cannot be cured, suitable medications and procedures, as well as

anticoagulant therapy, can go a long way to making life quite tolerable

and less hazardous.

Source

Atrial

fibrillation: strategies to control, combat, and cure. NS. Peters,

RJ. Schilling, P. Kanagaratnam, et al., Lancet, 2002, vol. 359,

pp. 593--603